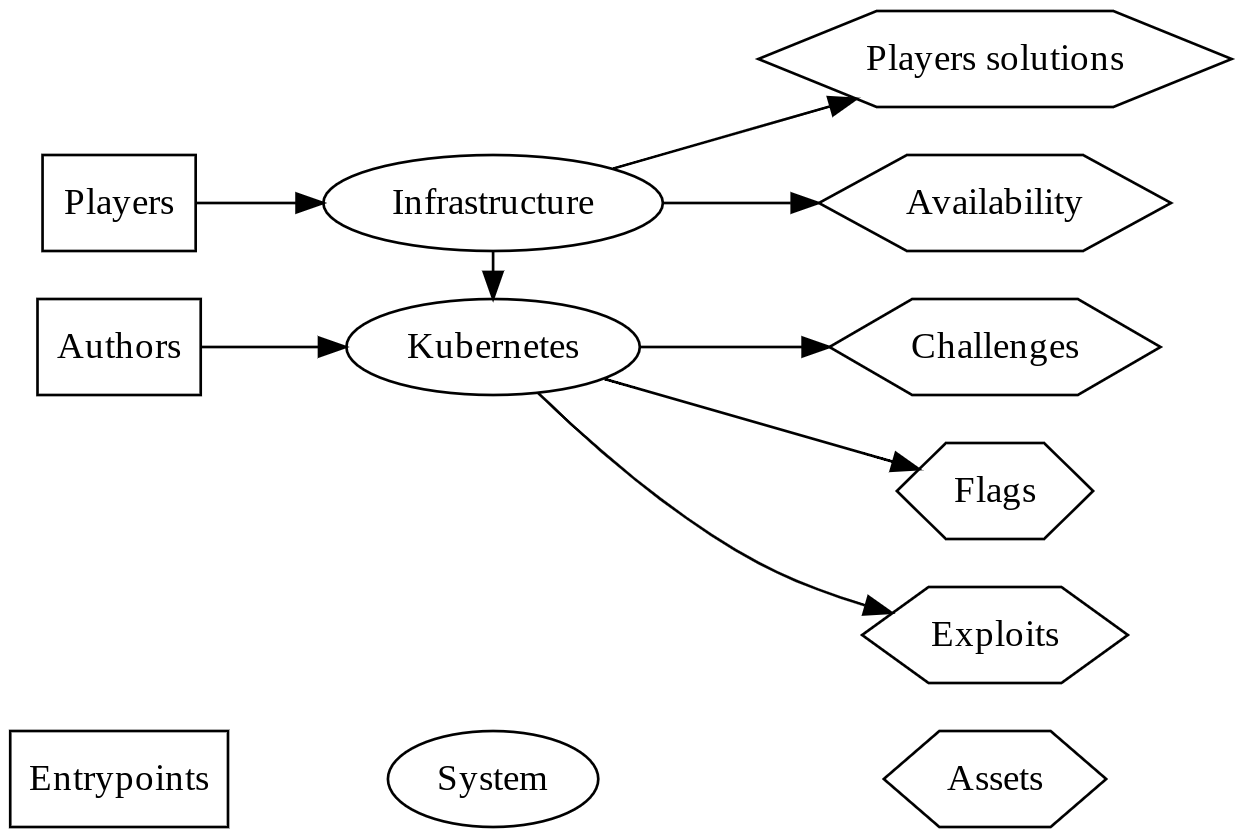

kCTF is a Kubernetes-based infrastructure in which authors are able to expose CTF challenges with security vulnerabilities like SQL injection or even challenges involving code execution. kCTF provides tools that make it impossible for an attacker to disturb the challenge, sabotage it, or gain an advantage over other players. To this end, the infrastructure provides tools for sandboxing and isolating every instance of a challenge from other users.

The assets that kCTF manages are:

- The flags: If an attacker gains access to the flags, this would undermine the whole competition. Recovery from this state, if detected, could be as simple as rotating the challenges.

- The challenges: If an attacker gains access to the challenge source code (when unintended), this could unfairly benefit the attackers. Recovery from this state could be impossible for challenges where the source code is meant to be secret.

- The exploits: In order to ensure that challenges are working, the infrastructure asks authors to provide an exploit to serve as a healthcheck. Recovery from this state is impossible, as this leaks the solutions to the tasks.

- Player solutions: Similar to exploits, if an attacker is able to read the solutions of other players, this could undermine the competition. Recovery from this state is also impossible.

- Availability: If the task or the infrastructure suffer a Denial of Service attack, this would have the consequence of losing the competition. Recovery from this state might be too expensive.

The players interact with the challenges through a Load Balancer configured in Google Compute Engine (GCE), which routes traffic to different virtual machines. A player's internet connection could be compromised (e.g. by a man-in-the-middle attack), or the players themselves could be compromised.

As such, the risks in this area are:

- A player's internet connection might be compromised

- Players could be compromised

Ways to limit these risks are:

- Players could connect to the tasks through HTTPS. However, there are currently no plans to implement this functionality.

- Players may 'tunnel' via VPN/SSH to a protected proxy device from which they then access the CTF.

The compromise of the players themselves is out of scope of kCTF's threat model.

The environment of every player should be isolated from other players. kCTF usually does this by creating a new Linux user namespace for every TCP connection. Some challenges, however, require persistent storage. Challenges that require persistent storage in between requests require relaxing these guarantees. This means that in those cases, challenges have to be carefully designed to ensure isolation between the sandboxed environment and the environment managing the shared storage. This is necessary, because as players solve the challenges, they might leave some traces in the infrastructure that other players could find and reuse to solve the challenges faster.

As such, the risks in this area are:

- Challenges might leave other players' solutions on the server.

- Isolation between users might not be configured properly.

Ways to limit these risks are:

- kCTF provides a per-TCP connection isolation mechanism by default.

- kCTF could provide a mechanism to isolate tasks per-team, rather than per-TCP connection. However, there are currently no plans to implement this functionality.

- kCTF could detect dangerous misconfigurations and warn authors. However, there are currently no plans to implement this functionality.

The infrastructure runs on Kubernetes, which supports automatic scaling and provisioning of resources. It also supports "proof of work" setups that can limit the impact of a malicious targeted attack. However, either through misconfiguration, or lack of monitoring, an attacker could exhaust the resources of a competition.

As such, the risks in this area are:

- Challenges might consume too many resources.

- Authors might respond too slowly to DoS attacks.

Ways to limit these risks are:

- kCTF automatically scales and limits the number of maximum nodes in a cluster.

- kCTF could automatically enable the proof-of-work when an attack is detected. However, there are currently no plans to implement this functionality.

The infrastructure itself runs on top of the Kubernetes control plane. Therefore, the system could be compromised from a challenge (e.g. through a vulnerability in the Linux kernel, or in Kubernetes itself).

As such, the risks in this area are:

- The Linux kernel or Kubernetes might have a vulnerability.

Ways to limit these risks are:

- kCTF automatically keeps its kernel up-to-date.

- kCTF could limit (through seccomp or similar) the kernel attack surface. However, there are currently no plans to implement this functionality.

The authentication between authors and Kubernetes is managed by Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE). Any vulnerability in GKE that allows unauthorized users to access GKE could gain access to all challenges code, the flags, and the exploits. In addition, any author that is compromised can undermine the competition in a similar fashion.

As such, the risks in this area are:

- The author could be compromised.

- Kubernetes or GKE might have a vulnerability.

Ways to limit these risks are:

- kCTF always keeps all clusters up-to-date, and follows hardening and configuration best practices.

- kCTF could use least-privilege principles, and limit access of authors to just their own tasks. Work to do this is tracked in issue #29.

The challenges are stored as Docker images in a private Docker registry on top of Google Container Registry (GCR). Any vulnerabilities in GCR or Google Cloud Storage (GCS) could result in the compromise of the challenges.

As such, the risks in this area are:

- GCS or GCR might have vulnerabilities.

- The project might be misconfigured.

Ways to limit these risks are:

- kCTF could limit the information in Docker images to the minimum possible. However, there are currently no plans to implement this functionality.

- kCTF could check the configuration to detect accidental misconfiguration. However, there are currently no plans to implement this functionality.

The flags are stored in the challenge images. The same considerations as outlined in the previous section apply.

The exploits are stored in the challenge images. The same considerations as outlined in the previous section apply.

In general, there are two types of attackers interested in attacking a system of this type:

- Attention-seeking malicious disruptive attackers

- Secretive cheating-driven attackers

Finding and exploiting a vulnerability in kCTF brings different benefits to attackers, usually reputational. The barrier of entry to perform an attack is usually the cost of finding the vulnerability. In order to increase the cost of these attacks, encouraging broad research by the well-intentioned security community on the same areas could result in a lower likelihood of an attacker paying the cost of a successful attack.

Conducting an attack usually consists of a cycle of trial and error. Although kCTF is open-source (which reduces this to some degree), in practice the cost of being stealthy directly correlates with the amount of preparation required. If the kCTF infrastructure provides thorough monitoring and alerting, this can increase the cost of preparation for attackers. Work to implement this is tracked in Issue #30.

Disrupting a competition done for the benefit of the security community is not immediately obvious, unless the competition itself, or the organizers, have managed to incentivise some of the members of the community to go through the effort to perform such an attack. As such, running a fair and high-quality competition is an easy way for organizers to prevent alienating and making skilled players convert from users to attackers.

kCTF attempts to address and balance several security concerns with usability and complexity. Understanding and improving the security of kCTF will be a constant process that will be addressed over time, based on the feedback of the community as different problems and solutions are discovered. This document will be kept up-to-date as new information arises.