My blog is down at the moment going some UI changes at the moment.

I wanted to talk about my recent project doing the Self Driving Car Engineer Nanodegree. In it we use a car simulator built by Udacity to gather some test data.

The project involves training a model and saving it to a file so that we pass it to a file Udacity provides, so that We can see if we cloned the behavior of our data or not.

I can't help but hear Liam Nesson's voice in my head.

> *The Model is nothing! Data is everything! The data to predict.*

So far in the courses and projects data has been given. Blue Apron for Machine Learning were shopping around is not even part of the equation.

I hate going to the grocery store because there are never good avocados. To find decency in this world of madness I have to go to the farmer's market, where you have to swim across a stream of people. Good guacamole requires the best ingredients and making good guacamole with bad avocados is machine learning with shit data.

It can be done and people may lie to your face telling you yes John your guacamole is good, but slowly you will affirm your suspicions as they leave it there untouched, forgotten, never to be loved. You'll taste it, and will lie to yourself Oh it is not so bad and will start wondering oh why is it harder to look at yourself in the mirror.

Stop wondering, is your shit guacamole ruining your life.

In a career were you constantly ask yourself 'Am I good enough?'... being in peace with your own self is the first step of traveling through the nine circles of hell.

Shopping for data feels eerily similar to getting Syrian Cheese and decent Hass Avocados for my guacamole. And to all those people out there who put milk or water on your guacamole... I throw my gauntlet at your treachery.

> *I fire up the Udacity Simulator, and it starts hogging my CPU as it saves 3 images per frame and appends a row to a logfile.*

I soon discover a new kind of dread as my lack of playing enough videogames has come to collect. I suck at gathering data, damned be my inability to move my thumb smoothly on a joystick on a track were the smallest error changes the steering wheel abruptly and makes me end in the bottom of a ditch.

I looked into the sky from my car in the bottom of the lake of track 1 of the simulator and thought, I need a solution for this.

I do the rational thing and find Vivek Yadav's awesome post on this project, he does all these amazing transformations to the images, but in the code I find comments of using only Udacity's data, this makes me sad initially for all the wrong reasons.

Oh for the glory of my stubbornness I will gather decent data, great data, the best data, no matter what, no matter how, and then I will preprocess all of it, each of it, carefully, methodically, surgically.

And so I set out on a fool's errand to extend the data to the firmament and beyond.

Modifying the images itself was a herculean tasks, just opening the directory of images would take a while as at least a few hundred images can be gathered in a couple of minutes.

So then I say, let's dump all the images into folders, and all the folders into other folders, and then have some script do some magic and join that data into one massive logfile. Then if we need new images, we can use the simulator again! This turned out not to be such a bad idea as Udacity open sourced their simulator last week, making it possible for me to use the scripts again.

data

|-track1

|---backtrack_and_merge

|-----IMG

|-----driving_log.csv

|---data

|-----IMG

|-----driving_log.csv

|---merge_into_lane

|-----IMG

|-----driving_log.csv

|---straight_line

|-----IMG

|-----driving_log.csv

|-track2

|---end_of_road

|-----IMG

|-----driving_log.csv

|---regular

|-----IMG

|-----driving_log.csv

The script would go through all those folders and files and make a unified log at the top level.

driving_log_compiled_0.csv

driving_log_compiled_1.csv

driving_log_compiled_2.csv

driving_log_compiled_3.csv

driving_log_compiled_4.csv

driving_log_compiled_5.csv

driving_log_compiled.csv

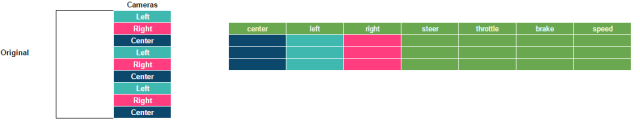

Which looks something like this:

| center | left | right | steer | throttle | brake | speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/center_2017_01_28_04_33_40_256.jpg | ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/left_2017_01_28_04_33_40_256.jpg | ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/right_2017_01_28_04_33_40_256.jpg | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.148237e-06 |

| ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/center_2017_01_28_04_33_40_357.jpg | ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/left_2017_01_28_04_33_40_357.jpg | ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/right_2017_01_28_04_33_40_357.jpg | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.704974e-06 |

| ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/center_2017_01_28_04_33_40_457.jpg | ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/left_2017_01_28_04_33_40_457.jpg | ./data\track1\backtrack_and_merge\IMG/right_2017_01_28_04_33_40_457.jpg | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1196939999999999e-05 |

So great, now we have the data and we need to pass it to a model using a generator. We do a few changes here and there to make it work on both Windows and Ubuntu and we finally arrive... at deep learning.

One final but important point regarding SGD is the order in which we present the data to the algorithm. If the data is given in some meaningful order, this can bias the gradient and lead to poor convergence. Generally a good method to avoid this is to randomly shuffle the data prior to each epoch of training.

> [Stanford Deep Learning Tutorial](http://ufldl.stanford.edu/tutorial/supervised/OptimizationStochasticGradientDescent/)

The implications of that quote dig deep into our data. Using scikit learn makes it trivial to shuffle some data. When preparing my ingredients to make my guacamole order is absolute key. I chop my cilantro, put it on the side, then comes a tomato, chop it up real good, and I keep working my way

x_train, x_test = train_test_split(image_index_db, test_size=0.4)

x_test, x_evaluate = train_test_split(x_test, test_size=0.4)

x_train = shuffle(x_train)

et voilà!

But that's assuming we have a nice image_index, a magical array of data, as gentle as a butterfly, as powerful as a bulldozer ready to tear down all in it's path.

The entire CSV file is on my data 4 mb, and even if I extended the data massively it wouldn't go as far as 200 mb. So loading the entire CSV using pandas is not a bad move, this creates our table of truth.

Assume the table at the top is our CSV file and we have 3 rows. The Simulator stores 3 images per frame, one for the left camera, another for the right camera, and the center camera.

> *Mapping all those images in those 3 rows is as simple as doing `len(rows*cameras)` which should give us `9`.*

This is pretty convenient as of 3 rows we can generate use all the images, shuffle them, break them into test set, train set, whatever set.

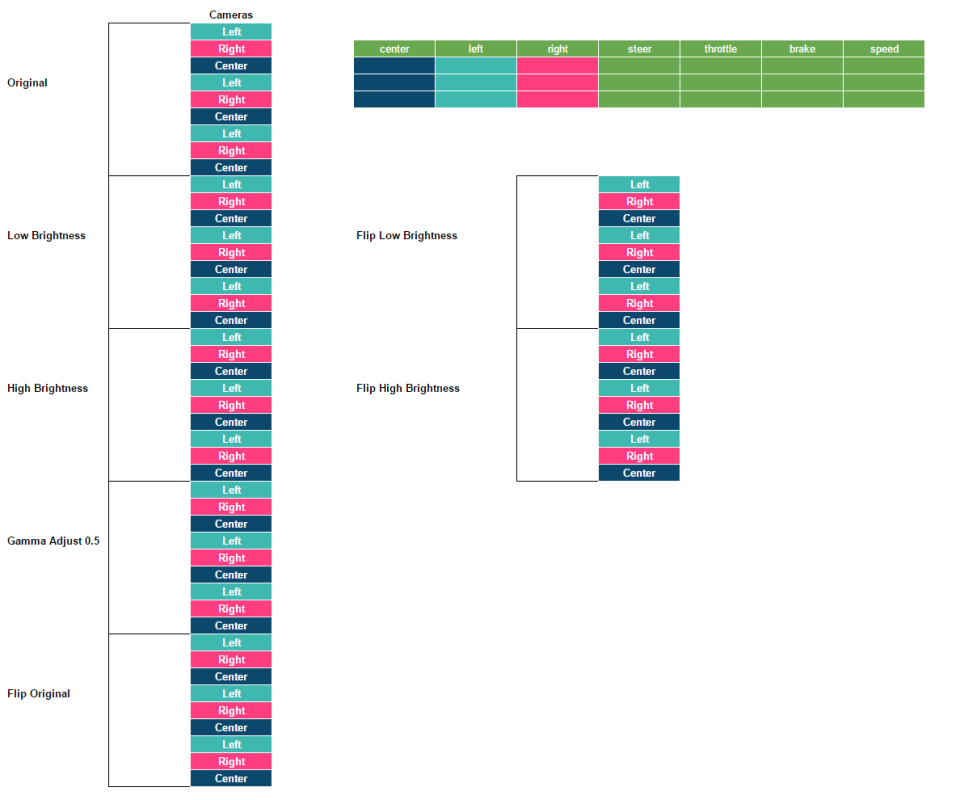

We're still not done with our 9 images. We can make them less bright, more bright, adjust the gamma factor, flip them, pop them, twist them.

And this is where the index gets useful.

> *We just turned `9` images into `9 x Number of transformations`, in this case `63` different images.*

We have used Python for all of Term 1, if we were on C++ this is possible doing function pointers that map to your transforms, delegates in C#, and Interfaces in Java. Each language it's going to have it's own perks but right now be sure that I'm cheating, because doing this in Python is a joke.

def get_images(p='./data'):

""" Image transforms will be done on the fly.

To shuffle our dataset we need the full list of images.

"""

logfile = processing.data_validation(p) # this line makes sure there is a log and it's valid

df = read_log(logfile, skiprows=1) # this one reads the log using pandas read_csv

N = len(df.index) # our rows

# D_c is a map to our cameras

D_c = {

0: 'left',

1: 'right',

2: 'center'

}

N_c = len(D_c) # left, right center cameras

# The features are the other columns that are not files to images

columns_w_features = processing.get_names()[N_c:]

# Our map of transforms, each one is a function

D_t = {

0: original,

1: low_brightness,

2: high_brightness,

3: gamma_correction_05,

4: gamma_correction_15,

5: gamma_correction_20,

6: gamma_correction_25,

7: flip_original,

8: flip_low_brightness,

9: flip_high_brightness,

10: flip_gamma_correction_05,

11: flip_gamma_correction_15,

12: flip_gamma_correction_20,

13: flip_gamma_correction_25

}

N_t = len(D_t) # transforms we will be applying

N_images = N*N_c*N_t

# Our powerhouse index

images = list(range(0, N_images))

# get_image_data is a util function that receives an index and returns all the info

# see below

get_image_data = image_getter(df, N, N_c, N_t, D_c, D_t, columns_w_features)

return images, get_image_data, N*N_cThe utility function to get the image info from an index is called a curried function.

def image_getter(df, N, N_c, N_t, D_c, D_t, features):

""" Setups a function with the fields we need

df: dataframe received from csv

N: total images in dataframe

N_c: Number of different camera pictures

N_t: Number of transforms to be done

D_c: Maps Int -> Camera String

D_t: Maps Int -> Transform function

features: Array of features to retrieve

returns: Function to get images based on index

"""

def getter(image_index):

""" Curried function that receives an Int Index

and returns properties of that image

image_index: index of the image to use

returns: Tuple(

relative path to image,

feature set of the image,

transform function,

camera string

)

"""

image_camera = image_index % N_c

image_transformation = image_index // (N * N_c)

image_row = image_index // (N_c*N_t)

return df.loc[image_row, D_c[image_camera]], df.loc[image_row, features].as_matrix(), D_t[image_transformation], D_c[image_camera]

return getterI 💖 Python

Code for the specific transforms and how to do them using OpenCV is in the Github repo.

For creating the generator to feed images to Keras we need an extra piece in the puzzle, the Batch Size.

When you go out to eat tacos in Mexico, you usually pimp them with proper vegetables and salsas, the crux of it is that you have started a time bomb and now you have to eat your tacos under a timeframe until they become a mushy set of tortilla liquid and meat. So what do you do as an expert gentleman of tacos? You prepare them in batches, and only you know the appropiate amount of tacos you can shove into your mouth in a specific timeframe. Over time you develop experience and you realize that 2 tacos per batch may work for Jimmy, but not for you, you eat 3 tacos per batch.

def get_images_generator(images, image_getter, BATCH_SIZE):

""" The generator of data

returns: Tuple(

numpy array of BATCH_SIZE with images in it,

numpy array of steering angles

)

"""

# Numpy arrays as large as expected

IMAGE_WIDTH = 320

IMAGE_HEIGHT = 160

CHANNELS = 3

batch_images = np.zeros((BATCH_SIZE, IMAGE_HEIGHT, IMAGE_WIDTH, CHANNELS))

batch_features = np.zeros(BATCH_SIZE)

i = 0

for image_index in images:

image, features, transform, camera = image_getter(image_index)

features, camera = adjust_properties_per_transform(features, camera, transform)

payload = transform(image)

features = adjust_angle_per_camera(features, camera)

if payload is not None and features[0]:

batch_position = i % BATCH_SIZE

batch_images[batch_position] = payload

batch_features[batch_position] = features[0]

i += 1

if batch_position+1 == BATCH_SIZE:

yield batch_images, batch_featuresYou may be wondering what adjust_properties_per_transform and adjust_angle_per_camera do. Some transforms will make some adjustments to the steering angle and the camera, and some cameras will make adjustments to the steering angle too. Refer to Vivek Yadav's awesome post for more info.

The bad thing about dealing with files is that one of them may return None due to some other process locking the file.

John needed to modify the evidence documents so that his plans would come to fruition. He broke into the building, shrouded in darkness. As he made his way through the documents room he found the first cabinet, it said 'December 1987', the date he commited those horrific crimes. He pulled out 200 files from the cabinet and took them to the closest table, and turned on the light, and started ordering the files, marking them, and preparing for the signature forgings, text deletions, and the whole set of things he was about to do to clear himself and his company.

John never returned a file to the cabinet, until he was done with everything he wanted with it.

Be like John.

def get_batch_properties(images, image_getter):

""" Order the images and the stuff we are going to

do to them in a dictionary for easy processing

images: a list of integers

image_getter: a function, receives an integer,

returns image data and what to do to the image

"""

r = {}

for i in images:

image_path, features, transform, camera = image_getter(i)

if image_path not in r:

r[image_path] = [(transform, features, camera)]

else:

r[image_path].append((transform, features, camera))

return r

def get_images_generator(images, image_getter, BATCH_SIZE):

""" The generator of data

returns: Tuple(

numpy array of BATCH_SIZE with images in it,

numpy array of steering angles

)

"""

# Numpy arrays as large as expected

IMAGE_WIDTH = 320

IMAGE_HEIGHT = 160

CHANNELS = 3

batch_images = np.zeros((BATCH_SIZE, IMAGE_HEIGHT, IMAGE_WIDTH, CHANNELS), np.uint8)

batch_features = np.zeros(BATCH_SIZE)

begin_batch = 0

N = len(images) + 1

while begin_batch+BATCH_SIZE < N:

i = 0

batch_dictionary = get_batch_properties(images[begin_batch:begin_batch+BATCH_SIZE], image_getter)

for img_path in batch_dictionary.keys():

img = cv2.imread(img_path)

for transform, features, camera in batch_dictionary[img_path]:

features_adjusted, camera_adjusted = adjust_properties_per_transform(features, camera, transform)

payload = transform(img)

features = adjust_angle_per_camera(features_adjusted, camera_adjusted)

batch_position = i % BATCH_SIZE

batch_images[batch_position] = payload

batch_features[batch_position] = features[0]

i += 1

begin_batch += BATCH_SIZE

yield batch_images, batch_featuresOnce the images are inserted into the numpy matrix all kinds of things happen, so we need to verify that this thing will return what we need in the way the Keras Model is expecting it, a batch of images and steering angles.

Writing a test is not that trivial because it requires some matplotlib.pyplot weirdness, which fortunately I have some experience with.

def test_generator():

image_index_db, image_getter, _ = get_images('./data')

shuffled_images = shuffle(image_index_db)

BATCH_SIZE = 30

sauce_generator = get_images_generator(shuffled_images, image_getter, BATCH_SIZE)

for i, p in enumerate(sauce_generator):

rows = 5

cols = BATCH_SIZE // rows

# Generate a figure of ROWS X COLS images, in this case 5 x 6 = 30

fig, axes = plt.subplots(rows, cols)

for j, (img, feature) in enumerate(zip(p[0], p[1])):

# axes[row, col]

ax = axes[j // cols, j % cols]

ax.imshow(img)

# The legend of the image, I just want to see the feature

s = 'Steer %.5f' %feature

label = '{steer}'.format(steer=s)

ax.set_title(label)

# Don't show the XY axes, we already know the dimension of the images

ax.axis('off')

# Increase the size between rows

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.5)

# Show the image

plt.show()

# Don't do this for all the Dataset otherwise you will die (it's more than 400k images)

if i > 10:

breakWe also want to see images with the Modified cameras and the transform that was applied, but this has to be in the generator itself since the info is constrained in there (and no we don't want to get it out).

def get_images_generator(images, image_getter, BATCH_SIZE, DEBUG=False):

""" The generator of data

returns: Tuple(

numpy array of BATCH_SIZE with images in it,

numpy array of steering angles

)

"""

# Numpy arrays as large as expected

IMAGE_WIDTH = 320

IMAGE_HEIGHT = 160

CHANNELS = 3

batch_images = np.zeros((BATCH_SIZE, IMAGE_HEIGHT, IMAGE_WIDTH, CHANNELS), np.uint8)

batch_features = np.zeros(BATCH_SIZE)

begin_batch = 0

# Instead of While true just iterate as long as the batch is less than N

# If we miss one batch due to batch size * samples < total images it's not so bad

# For now

N = len(images) + 1

while begin_batch+BATCH_SIZE < N:

i = 0

batch_dictionary = get_batch_properties(images[begin_batch:begin_batch+BATCH_SIZE], image_getter)

if DEBUG:

rows = 5

cols = BATCH_SIZE // rows

# Same as before, initialize the 5 X 6 (or 12) images

fig, axes = plt.subplots(rows, cols)

for img_path in batch_dictionary.keys():

abs_path = os.path.abspath(img_path)

img = cv2.imread(abs_path)

for transform, features, camera in batch_dictionary[img_path]:

features_adjusted, camera_adjusted = adjust_properties_per_transform(features, camera, transform)

payload = transform(img)

steer = adjust_angle_per_camera(features_adjusted, camera_adjusted)

if DEBUG:

# i is the current img, get axes[row, col]

ax = axes[i // cols, i % cols]

ax.imshow(payload)

# The verbose label we need, but not the one we want

s = 'Steer %.5f' %steer[0]

label = 'Camera - {camera}\nTransform - {transform}\n{steer}'.format(camera=camera_adjusted, transform=transform.__name__, steer=s)

ax.set_title(label)

# Img Dimensions are useless (320x160)

ax.axis('off')

batch_position = i % BATCH_SIZE

batch_images[batch_position] = payload

batch_features[batch_position] = steer[0]

i += 1

if DEBUG:

# We are adding 3 lines of text we need moar space

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.5)

plt.show()

begin_batch += BATCH_SIZE

print('new begin: ', begin_batch)

yield batch_images, batch_featuresBuilding the Neural Network itself has certain constraints. The model can be run by the CPU or GPU and both have their caveats.

When building my network for the CPU I usually don't worry about memory, so I can build my network and arbitrarily select the neurons per layer. This is comfortable, but too much freedom is bad for the soul. Furthermore the CPU takes considerably more time to train a network than a GPU.

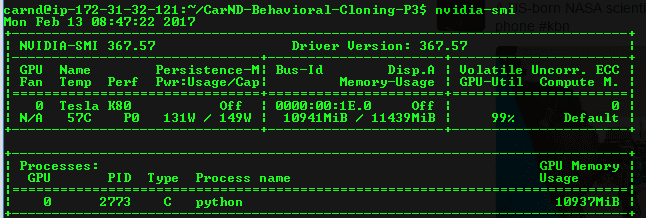

When building for GPU things become more interesting. I have a MSI Stealth Pro laptop from 2014, it has a Nvidia GTX 870M GPU in it, and the GPU only has close to 3GB of memory in it. Furthermore nvidia-smi doesn't work on my GPU.

To check that my GPU is doing something:

$ nvidia-settings -q GPUUtilization -q useddedicatedgpumemory

Or if I want to see how it changes:

$ watch -n0.1 "nvidia-settings -q GPUUtilization -q useddedicatedgpumemory"

It's important to understand these numbers before trying out a p2.xlarge machine on AWS with a K80 because the size of the network can change for 12GB of memory. The only reason is because training may take hours. According to some posts on forums and even Vivek's we see that training for a lot of epochs causes bad results, which is something we need to prepare for.

To check GPU on a g2.2xlarge or p2.xlarge:

$ nvidia-smi

Or if I want to see how it changes:

$ watch -n 0.1 nvidia-smi

This is what I get if I create layers that need more memory than my GPU can handle.

name: GeForce GTX 870M

major: 3 minor: 0 memoryClockRate (GHz) 0.967

pciBusID 0000:01:00.0

Total memory: 2.95GiB

Free memory: 1.43GiB

I tensorflow/core/common_runtime/gpu/gpu_device.cc:906] DMA: 0

I tensorflow/core/common_runtime/gpu/gpu_device.cc:916] 0: Y

I tensorflow/core/common_runtime/gpu/gpu_device.cc:975] Creating TensorFlow device (/gpu:0) -> (device: 0, name: GeForce GTX 870M, pci bus id: 0000:01:00.0)

W tensorflow/core/common_runtime/bfc_allocator.cc:217] Ran out of memory trying to allocate 1.17GiB. The caller indicates that this is not a failure, but may mean that there could be performance gains if more memory is available.

W tensorflow/core/common_runtime/bfc_allocator.cc:217] Ran out of memory trying to allocate 1.17GiB. The caller indicates that this is not a failure, but may mean that there could be performance gains if more memory is available.

W tensorflow/core/common_runtime/bfc_allocator.cc:217] Ran out of memory trying to allocate 1.36GiB. The caller indicates that this is not a failure, but may mean that there could be performance gains if more memory is available.

The problem is not building the Neural Network, the problem is training it. Here is my first model:

def get_model():

model = Sequential()

model.add(Cropping2D(cropping=((50, 20), (0, 0)), input_shape=(160, 320, 3)))

model.add(Lambda(lambda x: (x / 255.0) - 0.5, input_shape=(90, 320, 3)))

model.add(Convolution2D(32, 3, 3,

border_mode='valid',

input_shape=(32, 32, 3)))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2)))

model.add(Convolution2D(32, 3, 3,

border_mode='valid'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2)))

model.add(Convolution2D(32, 3, 3,

border_mode='valid'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2)))

model.add(Flatten(input_shape=(32, 32, 3)))

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

model.add(Dense(128))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Dense(1))

model.add(Activation('softmax'))

return modelI did a few recommendations from Udacity. If I really wanted to mess with it I would have applied Inception Modules, which worked great in my previous project and I'm still figuring out how to implement them in Keras.

> *A run of the model training and validation, notice the number of images in the training, validation and evaluation sets*

In total we have 818,580 images. We have 19,491 rows in our dataset, which means 58,473 total image files, which means 818,622 after applying transforms.

The reality is we can't do this, there are too many images to process and our indexes may clash and end up reading the same file. So we can shave of some images by not doing an evaluation run, here is why.

In a hackathon it may not matter what you use, sometimes it's better to just fake the entire thing, sometimes it's not. It depends on the judges, which is very implicit and depends on their bias towards you or your team.

In this project the objective is to clone the behavior, not to process all the images. Which means you are going to have a massive difference when it comes to your model vs your steering angles. To repeat the behavior the best bet would be to have the same data repeated again and again, and this is a wild conjecture.

A good chef knows the states to reach chicken coction in which the meat goes from raw and salmonella prone to perfect and rapidly declines into a bag of sand that is barely digestible, overfitting never has been represented any better.

So it's important to keep checking the temperature, the shape, the searing, everything needs to be in order at all times.

> *One of the best chef tools is `nvidia-smi`.*

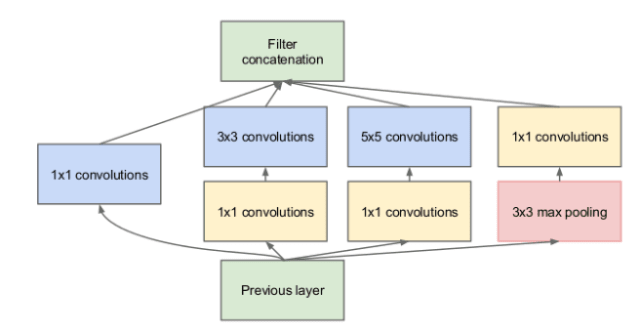

In 2014 Google presented GoogLeNet, a neural network made of 22 layers that looks something like this:

I have never trained such a massive network but I want to build a smaller version with less Inception modules. An inception looks like the following:

Which you may see it on the Deep Learning Course on Udacity as follows:

Inception worked really well for me in the past, so I want to take it out for a test drive on this project, at least to some exted, and the first step is to scrap the Sequential() model. One of the recommendations that caught my eye on Deep Learning1 is that gathering more data (or better data) is a more prefered route rather than changing the model.

So I'm doing Inception for pure learning purposes. What? Learning is what pushes everything, how do you think the guy who did the first deep fried chocolate covered bacon wrapped ice cream popsicle came up with that?

In general I try to use the largest Batch size as I can but I have not reached to a point where I can say if the Adam Optmizer works better due to that or not. On another study on Batch Normalization2 it establishes that each layer is affected by parameters of preceding layers, causing that small changes on the network amplify as it becomes deeper. As we can see from GoogLeNet... it's pretty fucking deep.

Furthermore the researchers found that including some normalization only caused bias to be distributed to compensate for the normalization, rendering the normalizatio ineffective. In the end they recommended to add normalization for any parameter values so that the network always produces activations in the desired distribution (0-1).

My frugal inception model looks as follows:

def get_model():

img_input = Input(shape=(160, 320, 3))

x = Cropping2D(cropping=((50, 20), (0, 0)), input_shape=(160, 320, 3))(img_input)

x = Lambda(lambda x: (x / 255.0) - 0.5, input_shape=(90, 320, 3))(x)

x = conv2d_bn(x, 8, 3, 3)

x = conv2d_bn(x, 16, 3, 3)

x = MaxPooling2D((3, 3), strides=(1, 1))(x)

# Inception Module 1

im1_1x1 = conv2d_bn(x, 16, 1, 1)

im1_5x5 = conv2d_bn(x, 16, 1, 1)

im1_5x5 = conv2d_bn(im1_5x5, 8, 5, 5)

im1_3x3 = conv2d_bn(x, 16, 1, 1)

im1_3x3 = conv2d_bn(im1_3x3, 8, 3, 3)

im1_max_p = MaxPooling2D((3, 3), strides=(1,1))(x)

im1_max_p = conv2d_bn(im1_max_p, 16, 1, 1)

im1_max_p = Reshape((88, 318, 16))(im1_1x1)

x = merge([im1_1x1, im1_5x5, im1_3x3, im1_max_p],

mode='concat')

# Inception Module 2

im2_1x1 = conv2d_bn(x, 16, 1, 1)

im2_5x5 = conv2d_bn(x, 16, 1, 1)

im2_5x5 = conv2d_bn(im2_5x5, 8, 5, 5)

im2_3x3 = conv2d_bn(x, 16, 1, 1)

im2_3x3 = conv2d_bn(im2_3x3, 8, 3, 3)

im2_max_p = MaxPooling2D((3, 3), strides=(1,1))(x)

im2_max_p = conv2d_bn(im2_max_p, 16, 1, 1)

im2_max_p = Reshape((88, 318, 16))(im2_1x1)

x = merge([im2_1x1, im2_5x5, im2_3x3, im2_max_p],

mode='concat')

# Fully Connected

x = AveragePooling2D((8, 8), strides=(8, 8))(x)

x = Dropout(0.5)(x)

x = Flatten(name='flatten')(x)

x = Dense(1, activation='softmax', name='predictions')(x)

return Model(img_input, x)My computer fights bravely yet foolishly, spitting out blood in the form of tensorflow/core/common_runtime/bfc_allocator.cc:275] Ran out of memory trying to allocate 71.74MiB until it finally croaks while holding my hand and looking at my eyes as it gently whispers...

tensorflow.python.framework.errors_impl.ResourceExhaustedError: OOM when allocating tensor with shape

I push it down the cliff with the tip of my foot and watch it fall as it hits itself againts the rocks.

We're going to need a bigger GPU.

Deep Learning is a lovely thing, it's this massive system of matrices doing work for you, whether they are going to do it right or wrong is going to depend on your ability to take their shit. Right now I am going through some process that I see an if-else and I want to plug a Neural Network to it to see what happens... I'm calling it noobness stage.

1: Bengio, Yoshua, Goodfellow, Ian J & Courville, Aaron (2015). Deep learning.

2: Sergey Ioffe and (2015). Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing. CoRR, abs/1502.03167.