Data extraction, transformation, manipulation, and analysis of the Making and Knowing Project's core dataset of the Digital Critical Edition, Secrets of Craft and Nature. The working files and data are housed in m-k-manuscript-data.

The Manuscript class represents a python version of BnF Ms 640. It contains a list of Entry objects, which hold the raw XML data from each entry along with some other data such as categories, title, ID, and properties.

When Manuscript is instantiated, it reads a folder full of folios and processes it into its component entries, each of which becomes a Entry object.

update.py is a script that generates the Manuscript object with all the folders in the ms-xml directory of your local m-k-manuscript-data repository and then writes derivative forms and the entry-metadata table to your local m-k-manuscript-data repository.

The derivative files/folders are:

- allFolios/: for each version, a single XML file containing each folio concatenated together

- entries/: for each version, every entry as a single file in both XML and TXT formats

- metadata/entry-metadata.csv: listing of the properties of each entry, including IDs, headings, and semantic tags (the significant properties of the manuscript as defined by the M&K Project editors), which is used to generate the "List of Entries" page on the edition640.makingandknowing.org website

- ms-txt/: for each version, every folio as a single file in TXT format

Note for TXT versions:

- utf-8 encoding

- ampersand (&) is rendered in its literal form rather than the character entity

& - text marked as

<add>(additions),<corr>(corrections),<del>(deletions),<exp>(expansions), or<sup>(supplied) in the XML files under ms-xml is retained - figures and comments are absent and unmarked

These are detailed instructions for how to use update.py. For simpler steps to updating derivatives in m-k-manuscript-data, see the README in that repo.

-

Update

m-k-manuscript-datamaster branch:cdtom-k-manuscript-datadirectorygit fetchgit pullto make sure you are up to date- Checkout a branch:

git checkout -b [name of branch]-- though you will be running code in themanuscript-objectdirectory, its output will be written to them-k-manuscript-datadirectory (i.e., the changes will be made in that directory)

-

Navigate to your local

manuscript-objectdirectory:cdtomanuscript-objectdirectory -

Make sure you're on the correct (usually master) branch by typing

git status. If you're not in the correct branch, typegit checkout -b [BRANCH_NAME]. -

git fetch -

git pull -

Run update.py. Detailed instructions are below, but specific tasks are listed here:

- To regenerate all the derivative files from originals:

python3 update.py - To test update.py without generating any derivative files:

python3 update.py -d - To only generate specific derivatives:

python3 update.py [--all-folios] [--entries] [--metadata] [--txt], without the brackets - To generate a derivative and write its output to a folder of your choice:

python3 update.py <DERIVATIVE TAG> [PATH/TO/FOLDER], without the brackets- e.g.:

python3 update.py --metadata ./test-metadata/will writeentry-metadata.csvto thetest-metadata/directory instead of the default, which is themetadata/directory in your localm-k-manuscript-datarepo - NOTE: as of January 6th, 2021, this will break if you try to provide a path to a folder that does not exist.

- e.g.:

- To show the help message:

python3 update.py -h

usage: update.py [-h] [-d] [-v] [-b] [-a [ALL_FOLIOS]] [-m [METADATA]] [-t [TXT]] [-e [ENTRIES]] [path]

Generate and update derivative files from original ms-xml folios.

positional arguments:

path Path to m-k-manuscript-data directory. Defaults to the sibling of your current directory.

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-d, --dry-run Generate as usual, but do not write derivatives.

-v, --verbose Write verbose generation progress to stdout.

-b, --bypass Bypass user y/n confirmation. Useful for automation.

-a [ALL_FOLIOS], --all-folios [ALL_FOLIOS]

Update allFolios derivative files. Disables generation of other derivatives unless those are

also specified. Optional argument: folder path to which to write derivative files.

-m [METADATA], --metadata [METADATA]

Update metadata derivative files. Disables generation of other derivatives unless those are

also specified. Optional argument: folder path to which to write derivative files.

-t [TXT], --txt [TXT]

Update ms-txt derivative files. Disables generation of other derivatives unless those are also

specified. Optional argument: folder path to which to write derivative files.

-e [ENTRIES], --entries [ENTRIES]

Update entries derivative files. Disables generation of other derivatives unless those are

also specified. Optional argument: folder path to which to write derivative files.

Note: if you have multiple versions of Python 3 installed, specify that version when running bash commands. E.g., python3.7 instead of python3.

update from 2023/02/20: here I think it should be install "pip" instead of install "pip3" (it might be because I have a older version of python, still need to double check)

pip3 SHOULD specify using the version of python you have that is 3.0+ whereas pip is more general. So it is possible that for some users, install "pip" is sufficient, rather

- Clone the repositories into separate folders in the same directory:

git clone https://github.com/cu-mkp/m-k-manuscript-data

git clone https://github.com/cu-mkp/manuscript-objectE.g., after running these commands in a folder called, for example, 'mkp', you should see:

mkp/

m-k-manuscript-data/

...

manuscript-object/

...

update from 2023/2/20: here I did not see a folder called mkp, but I did see two seperate folder called m-k-manuscript-data and manuscript-object.

-

Run

python3 -m pipenv installto install dependencies to the pipenv shell. If you get a version error, trypython3 -m pipenv install --python [VERSION], where [VERSION] is the version of Python you just installed (e.g. 3.7.4). -

To enter the pipenv shell, run

python3 -m pipenv shell. To exit, press ^D or typeexit. Inside the pipenv shell, all outside dependencies for the repository are installed.

Helpful hint: If you just want to run a specific command (e.g. run a file) without entering the shell, use python3 -m pipenv run [COMMAND]. If you find yourself doing this often, consider adding an alias, e.g. so you can simply write: pipenv run python3 update.py.

If you are a little savvy with Python, you can interact directly with the Manuscript in a Python interpreter. Open up the Python interpreter, Jupyter Notebook, or iPython in the manuscript-object directory and enter the following:

> from manuscript import *

> m = Manuscript(utils.ms_xml_path)Now the Manuscript is held in memory with the variable name m. You can look at a particular entry like this:

> e = m.entries['tl']['p005r_2']And you can inspect various aspects about it:

e.texte.xml_stringe.properties

There are also several functions which are useful when interacting with entries:

> find_terms(e.xml, "env")

['window',

'street',

'window',

'window',

'street',

'pierced door of a closed room',

'sun']With a bit of Python, you can make complex queries about the manuscript this way.

> for id, entry in m.entries['tl'].items():

if len(find_terms(entry.xml, "env")) > 0:

print(id)

p003r_2

p003r_3

p004r_2

p004v_1

...

p169r_1

p170r_4

p170v_3Just like that, you get a list of all the entries with environment tags in them!

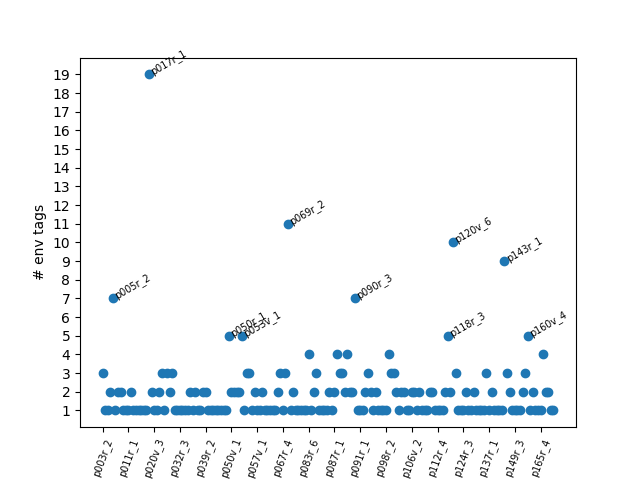

If we store some data in a list, we can plot the number of env tag occurrences by entry:

> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

> ids = []

> n_terms = []

> for id, entry in m.entries['tl'].items():

terms = find_terms(entry.xml, "env")

if len(terms) > 0:

ids.append(id)

n_terms.append(len(terms))

> plt.scatter(ids, n_terms)

> plt.show()With a little extra formatting, you have a visualization of roughly where env tags appear in the manuscript!

We see that entry 17r_1 has a ton of environment tags. Why is this?

> e = entries['tl']['p017r_1']

> e.title

On the gunner

> e.properties["environment"]

['ditch casemates',

'private houses',

'small towns',

'fortresses of little importance',

'casemates',

'trenches',

'edge of the ditch',

'gabions',

'garrets topped with a tower',

'city',

'city',

'barricade',

'house or elsewhere',

'cities',

'houses',

'walls',

'tower',

'houses',

'houses']So this is an entry discussing how gunners interacted with various environments in order to defend or attack them! It looks pretty long. How many characters is it?

> len(e.text)

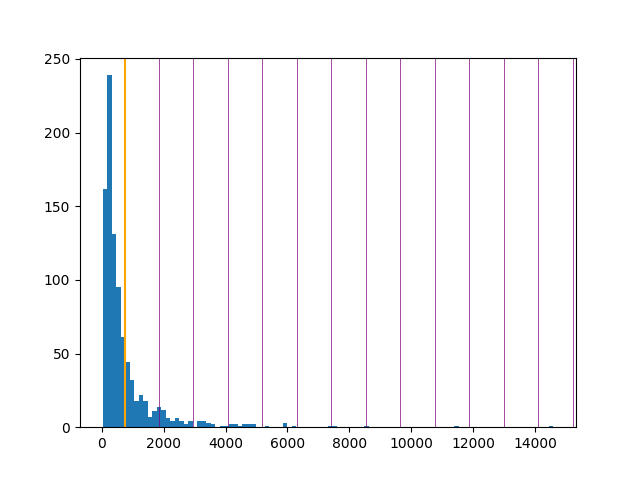

14595Looks like a big number, but how much is that in context?

> lengths = [len(entry.text) for entry in m.entries["tl"].values()]

> average = sum(lengths) / len(lengths)

> average

732.9827586206897Wow! Compared to the average, this entry is super long! But that doesn't tell us anything about the actual distribution.

> import math

> sd = math.sqrt(sum((x - average)**2 for x in lengths) / len(lengths))

> sd

1114.6637780356928Unsurprisingly, we have a pretty significant standard deviation.

> len(e.text) / sd

13.093634410297176So the length of entry 17r_1 is 13 standard deviations from the average entry in the manuscript!

It's very easy to go from here to a simple histogram showing the length distribution:

> plt.hist(lengths, bins=100)

> plt.axvline(average, color="orange")

> for x in range(1,14):

plt.axvline(average + x*sd, color="purple", linewidth=0.5)The orange line is the mean; the purple lines are standard deviations. That tiny blue blip around 14000 must be entry 17r_1.

Admittedly, this sort of statistic is not terribly informative on this kind of dataset, but possibilities are abound. Interacting with the manuscript is made simple and powerful by holding the entries in memory as a Python object.