Toward a generalized, blockchain-agnostic protocol for thin/light clients.

Abstract. Most Internet communications systems rely on accurate public key exchange to ensure their security. A man-in-the-middle (MITM) can compromise the security of these systems by replacing legitimate keys with their own as they travel to their destination. In the context of SSL/TLS, over 1200 organizations each have the ability to perform this attack for any website. Blockchains prevent these and other "non-fundamental" MITM attacks by associating keys and arbitrary identifiers without relying on third party trust. However, end-user devices cannot run blockchain full nodes due to resource constraints. Here we define a new thin client technique called Proof of Transition as a step toward definining a blockchain and technique agnostic thin client protocol for transfering most of the security properties of blockchain full nodes to resource constrained devices in a low-trust manner.

Table of Contents

- DNSChain's Revised Security Model

- Goals: Security + Agnosticism

- Comparing Thin Clients Techniques: SPV vs PoT

- Proof-of-Transition (PoT) Definition

- Generalized Thin Client Protocol

- Thin Client Threat Models

Note: From here on "proxy" and "DNSChain" are interchangeable.

DNSChain's original security model involved a trusted proxy with a MITM-proof channel established via public key pinning.

This technique offers significant improvement over today's HTTPS security model that relies on X.509. However, scaling a trusted-proxy model to all Internet users is challenging since not everyone may have a trustworthy DNSChain server to connect to.

The security model described herein modifies the old by relying on thin client techniques to reduce the amount of trust that is placed in the proxy that clients connect to.

Our focus is now on defining a blockchain-agnostic protocol for thin client techniques.

Security. Communications should be readable by invited participants only, and any tampering must be detectable. Blockchains make this possible.

Agnosticism. The protocol must be blockchain agnostic since:

- Any blockchain may become abandoned by the Internet community.

- The "ideal blockchain" is unknown and may not exist.

- Non-agnostic protocols promote potentially harmful centralization.

A thin client (or a light client) refers to software that downloads only a portion of the blockchain.1 This gives clients some ability to verify for themselves the authenticity of information within it.

The standard thin client protocol used by Bitcoin is called Simple Payment Verification (SPV). In this document, we will describe a new thin client protocol called Proof of Transition (PoT).

There may be yet other thin client techniques to be discovered. Our long-term goal (outside the scope of this document), is to help define a generalized thin client protocol flexible enough to accommodate as many techniques as possible.

There are many ways to do SPV, some better than others. The Namecoin developers put together a comprehensive document exploring the various different types of SPV modes that are possible.

Pros:

- Advanced UTXO-based SPV modes provide excellent security for accessing blockchain information without running a full node.

Cons:

- This technique is not always practical or available. Some blockchains may not support it and some devices may not make it feasible.

- Traditional SPV is succeptible to replay attacks, whereas PoT and UTXO-style SPV are not.

In PoT, clients download portions of the blockchain from the proxy on an as-needed basis and keep track of who owns the value for a given key. If the value changes, they require proof demonstrating the original owner authorized the transition.

Pros:

- Simple to implement and provides comparable security to SPV.

- Might support more types of blockchains because Merkle roots do not need to be stored in the blockchain (but see con about pruning).

Cons:

- Does not support full nodes that prune transaction history.

- Does not handle all large blockchain forks as gracefully as SPV.

- Not suitable for situations where identifiers are updated frequently because clients must process all transactions between the transaction they last saw and the current one.

We describe PoT not to claim it is better than SPV, but to explore the diversity of thin client techniques in order to help define a generic thin client protocol capable of supporting all of them.

The rest of this document will focus on defining Proof of Transition since plenty of literature on thin clients and SPV(+) already exists elsewhere.

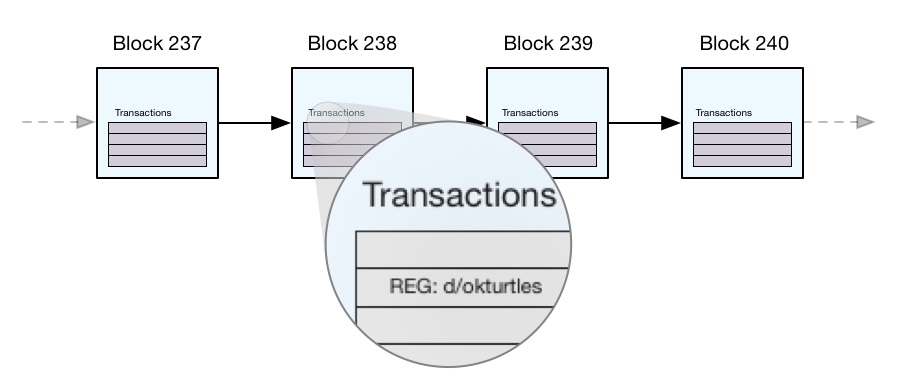

As the name suggests, blockchains are made of blocks chained together. Each block usually contains a list of transactions.

In Namecoin, .bit domains are mapped to the d/ namespace. So okturtles.bit can be registered by creating a transaction claiming ownership of d/okturtles (if no unexpired transaction already exist in the blockchain).

PoT behavior on initial identifier lookup

When a client looks up an identifier for the first time (such as okturtles.bit), the proxy sends the following information (all of which is cached by the client):

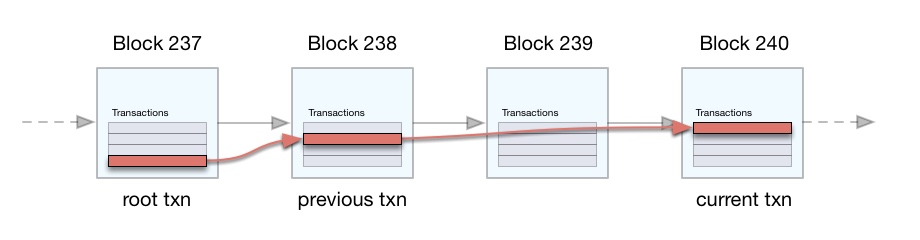

- The root transaction, which contains the most recent registration of the identifier.

- The current transaction, representing the current value and current owner of the identifier. This value is added to a Bloom filter (that's associated with the root) to prevent replay attacks (discussed later in Forking Considerations and Thin Client Threat Models).

The security of PoT rests on establishing the validity of the root transaction, and therefore clients must retrieve the information above from at least two different proxies and verify that all responses match.

Securing the connection to proxies and reducing collusion risk

Connections to proxies are secured via public key pinning, similar to how browsers come with a list of Certificate Authorities (CAs) key pins.

Whereas security in today's CA system decreases with the more CAs there are, the opposite is true with blockchain-based architectures: the more proxies that are queried, the greater the security.

Of greatest significance is that blockchains can be run and used by anyone to authenticate arbitrary Internet connections and end users can specify which proxies they trust. If the end user does not specify a trusted proxy, two or more proxies (belonging to separate organizations) can be chosen at random from a predefined list.

To prevent the likelihood of colluding proxies, the proxies that are used can be periodically changed (re-chosen at random). If a previously chosen set of proxies had colluded on the first-lookup of an identifier, this would be discovered once a proxy outside of that colluding set is used.

PoT behavior when an identifier's value changes

When a previously queried identifier changes, PoT requires a proof be sent demonstrating the previously known owner authorized that change.

If the observed change is not the result of a fork, the entire protocol sequence would be as follows:

- Client queries a proxy for the value of an identifier and receives a transaction that is different from its locally cached version.

- Client sends its cached transaction (the one labeled previous in the figure below) to the proxy and requests a PoT to the current transaction it received in (1).

- Proxy responds with the list of transactions between the previous txn sent in (2) and the current txn in (1).

- Client verifies the transaction chain:

- If verification is successful, the entire transaction chain is efficiently memorized by a Bloom filter and then discarded (except for the new current transaction for the identifier).

- If verification fails, an attack or data corruption is assumed. Client can either retry or switch to an honest proxy.

In the scenario depicted below, steps 2-3 are skipped because there are no transactions between previous and current, and so the PoT can be instantly verified at step 1:

Forking Considerations

Clients never discard the root transaction they receive in order to handle legitimate forks in the blockchain that override the previous cached transaction.

If such a situation occurs, the PoT protocol works exactly as described previously, except Step 3 is now:

- The proxy sends a specially marked "fork PoT" that contains the entire transaction chain from the root to the current. The client verifies the signatures in the transaction chain and verifies that the Bloom filter has not seen the transaction at the end of the chain (the new current).

- If signature verification fails, the client treats it as either an attack or data corruption and lets the user decide whether to retry or switch to a different proxy.

- If the Bloom filter reports it's seen all of the transactions, this indicates either a replay attack or a poorly configured Bloom filter (making the probability of a false positive too high). Recovery proceeds the same as when recovering from a root mismatch (described next).

A dangerous situation can occur when a fork is so long that the block containing the root is overwritten. If such a fork were to occur, the thin client would have no way to obtain a PoT. This scenario is depicted in the figure below (where the red blocks are now the longest chain):

Clients have no way to distinguish this situation from an actual attack (where the proxy fabricates a fork to insert its own key as the root), and must therefore treat it as such.

Recovery could proceed as follows:

- Inform the user that they may be under attack by the proxy they are using.

- Present a GUI to the user that allows them to choose two or more other proxies to query to re-establish a new root.

- Query those two proxies in addition to four other randomly chosen proxies to establish a quorum for a new root for the identifier.

- If quorum achieves 100% agreement, override the root. If the original proxy disagrees with the quorum, report it and use one of the two user-selected proxies in its place.

- If quorum fails to achieve 100% agreement, inform the user and let them decide what to do next.

This scenario should be extremely rare since most root transactions will be buried deep in the blockchain.

A generalized thin client protocol for Internet-wide use is our goal, but its definition is outside the scope of this particular document.

This document demonstrates that there may be many diverse ways to implement thin clients, and that is important because any generalized blockchain-agnostic thin client protocol must be flexible enough to accomidate arbitrary thin client techniques, including those yet to be discovered.

If you're interested in this topic we'd love to collaborate with you. Get in touch!

This section will be organized by threat type. We've done our best to describe the most significant ones but we might have missed something. If you notice something that should be here, please open an issue or send a pull request!

For another threat analysis by a team from Namecoin, please see:

Stealing identifiers

Identifiers can be stolen by attacking the blockchain network itself and censoring updates to an identifier until it expires.

Methods

- 51% attack (cpu based or stake based) on blockchain.

- Sybil attack on blockchain network.

- Global MITM attack on blockchain network to censor updates.

- Local MITM/DoS attack on the connection from the thin client to the network.

Significance

Small. The person trying to update their identifier's value would likely notice very quickly that the network wasn't accepting their updates and would probably raise a ruckus.

Difficulty

Generally extremely difficult to pull off because of the amount of time and resources required, but it also depends on the blockchain being attacked.

Thin Client Protocol Analysis

- SPV: if a thin client connects to compromised proxies, or if the connection to the proxies is compromised somehow, then updates from

thin client -> networkand fromnetwork -> thin clientcan be blocked. - PoT: same as SPV.

Mitigation

For global attacks on the network, there is nothing thin clients can do.

For local attacks, thin clients (of both SPV and PoT type) should attempt to connect to more nodes/proxies. However, if the attacker has complete control of the thin client's network it can prevent any connection it wants. If you think your connection is being censored, the best thing to do would be to try to bypass the MITM by tunneling your connection outside of its control (i.e. via VPN, Tor, etc.).

Censorship

Censorship can be used for various purposes, such as stealing identifiers (described above), or denying the existence of an identifier.

Methods: The methods are the same as those required for stealing identifiers.

Significance: Varies.

Difficulty: Low for blocking all identifiers, extremely high for blocking specific ones.

Thin Client Protocol Analysis

Both SPV and PoT may cache the existence of an identifier locally, however in PoT this is a requirement (whereas it is not in SPV). This means that in PoT a client that's visited a website before will know it existed at some point and cannot be told otherwise, whereas some implementations of SPV may be fooled into thinking an identifier never existed.

Both SPV and PoT thin clients can be prevented from seeing the latest updates to a blockchain.

However, both SPV and PoT do nothing on their own to prevent IP-based censorship attacks. That means even if a lookup succeeded, it does not mean you will be able to access that website.

Mitigation

Same as Mitigation for Stealing identifiers.

Privacy: Monitoring access of identifiers

Methods

- MITM attacks of almost any sort (doesn't even have to be on the connection between a thin client and a proxy, could simply be a reverse IP map).

- Ownership or compromise of the proxies/nodes that the thin client is connecting to.

Significance

Depends on how important it is to you whether someone knows who you are communicating with and what websites you are visiting.

Difficulty

Low. Anyone who can act as a MITM between you and the rest of the world can see what you are doing.

Thin Client Protocol Analysis

Both SPV and PoT leak information about the identifiers you are looking up.

Even if you were to run a full node and conduct lookups purely locally a MITM could still figure out who you are communicating with and what websites you are visiting simply by monitoring the IP addresses you connect to.

Mitigation

If privacy is of significant concern to you, there is no substitute for anonymizing networks like Tor. If privacy is of small but non-significant concern to you, run your own full node on a server and point you SPV/PoT thin client at it.

Replay Attacks

A replay attack is where outdated/expired identifier values (that actually exist in the blockchain) are sent back to the thin client.

Methods

- Compromise connection to proxy/full node via MITM attack.

- Compromise the proxy/full node itself.

Significance

Small to severe, depending on nature of attack.

- This attack can be used in tandem with a MITM attack to decrypt encrypted connections using a compromised key.

- It can also be used to force communication with a compromised account. Say you want to send money to an old friend whose credentials are in the blockchain, or visit a blockchain-based website. If their old contact information was compromised somehow you could be fooled into sending money to someone else.

Difficulty: Moderate.

Thin Client Protocol Analysis

- SPV: Traditional SPV techniques are succeptible to this attack. New SPV modes (like those that store the UTXO set in the blockchain headers) can prevent this attack from happening but may require special support by the blockchain.

- PoT: Clients use a Bloom filter per cached root to efficiently memorize all of the transactions they've seen; therefore this technique is immune to relay attacks. See Censorship attacks for a "replay" attack that could be done through censorship (applies to SPV as well).

Mitigation: Use PoT or UTXO-based SPV instead of traditional SPV.

Forgery

In other words, completely misleading clients as to the information stored in the blockchain.

Methods

- Compromising multiple proxies to force collusion between them.

- Targeted MITM attack on vulnerable clients within a small time window.

- 51% attack to reverse global blockchain history.

Significance: Extreme.

Difficulty: Very difficult.

Thin Client Protocol Analysis

All blockchain nodes, even full nodes, are vulnerable to forgery done by a 51%+ attack that reverses global history. Luckily this is extremely hard to do and in most cases would likely be noticed (although some blockchains are more vulnerable than others).

- SPV: If an SPV thin client is able to successfully download blockchain headers, there is no known mechanism by which to invent transactions that don't exist in the blockchain (short of breaking the cryptography involved). The window for attack is very small and only applies to thin clients that have not yet finished downloading the latest blockchain headers.

- PoT: If a thin client using PoT has previously requested an identifier, an adversary could mount the attack described in the section Forking Considerations, but the client would notice and compensate. If the client had not yet requested the identifier, an adversary would have to compromise all the proxies the client was communicating with (or the connections to them) and forge a false root (which would be detected once the proxy set is shuffled to include non-compromised proxies).

Mitigation

Blockchains and their communities should use whatever means necessary to prevent 51% attacks and pay attention to orphaned blocks (those no longer valid due to a fork).

For both PoT and SPV, this attack can be mitigated by connecting to trusted proxies managed by competent and security-conscious sysadmins, and the more the merrier.