- Introduction

- Smart Contract Storage Layout

delegatecall- Proxy Patterns

- Security Guide to Proxy Vulnerabilities

- Development Guide to Proxies

- References

Welcome to the Proxies & Upgradeable Smart Contracts repository by QuillAudits. This repository contains all the technical, theoretical and practical concepts, their explanations and implementations required to understand everything about the upgradeability of smart contracts in Solidity.

One thing the Blockchain is very often connected to is the immutability of data. For long time it was "Once it's deployed, it cannot be altered". That is still true for historical transaction information. But it is not true for Smart Contract storage and addresses.

By design, contract code on a blockchain is immutable. Though a key feature, it leads to difficulty when considering upgradeability. Newer entrants may wonder why “upgrading” on a blockchain is necessary. Inevitabilities requiring code changes still remain, including: bug fixes, patches, optimizations, feature releases, etc.

Before directly jumping into proxies and upgradeable contracts, we need to first understand the working of Solidity's delegatecall opcode and before understanding delegatecall, it would be helpful to see how the EVM saves the contract's variables in storage.

Contract storage layout refers to the rules governing how contracts’ storage variables are laid out in long-term memory. Almost all smart contracts have state variables that need to be stored long-term. There are 3 different types of memory in Solidity that developers can use to instruct the EVM where to store their variables: memory, calldata, and storage. Here, we'll be talking about the storage layout.

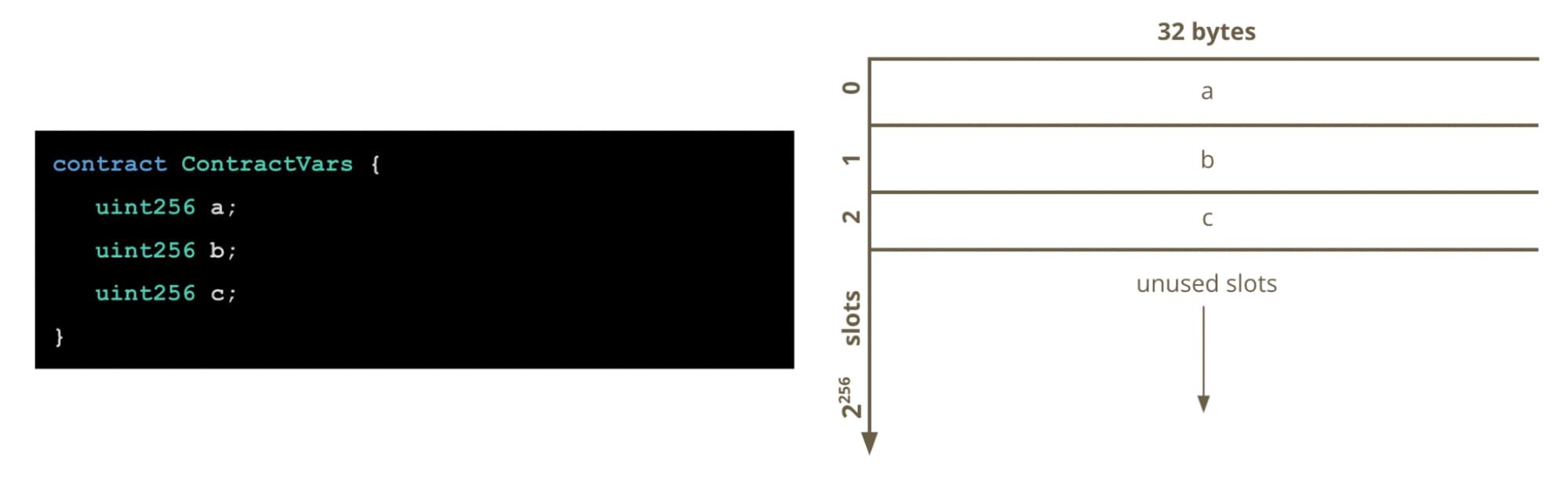

Each contract gets its own storage area which is a persistent, read-write memory area. Contracts can only read and write from their own storage. A contract’s storage is divided into 2²⁵⁶ slots of 32 bytes each. All slots are initialized to a value of 0.

Solidity will automatically map every defined state variable of your contract to a slot in storage in the order the state variables are declared, starting at slot 0. Here we can see how variables a, b and c get mapped to their storage slots.

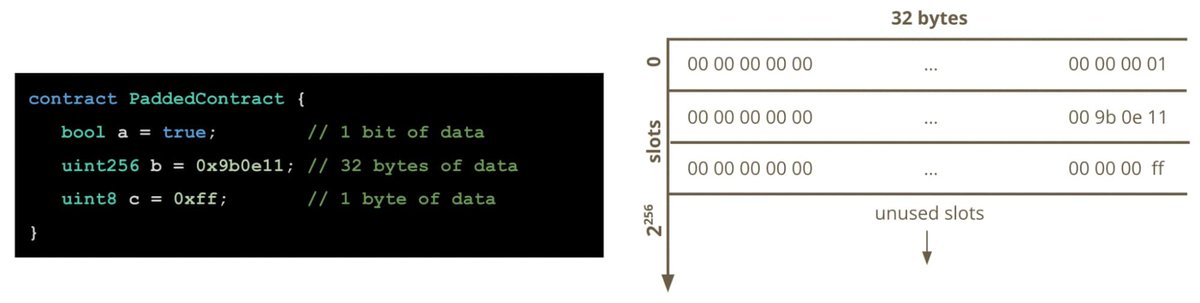

To store variables that require less than 32 bytes of memory in storage, the EVM will pad the values with 0s until all 32 bytes of the slot are used and then store the padded value. Many variable types are smaller than the 32 byte slot size, eg: bool, uint8, and address.

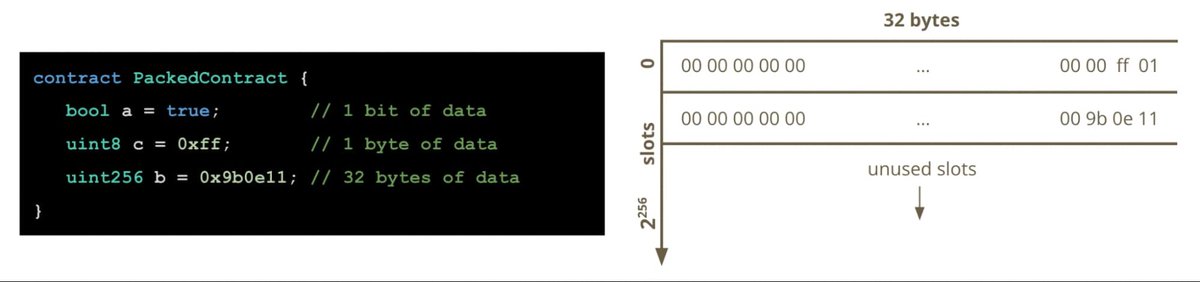

If we think carefully about the sizes of our contracts’ state variables and their declaration order, the EVM will pack the variables into storage slots to reduce the amount of storage memory that is used. Taking the PaddedContract example above we can reorder the declaration of the state variables to get the EVM to tightly pack the variables into storage slots. An example of this is shown in the PackedContract which is just a reordering of the variables in the PaddedContract:

However, there's a catch in packing the variables together instead of padding. The storage gas savings of tightly packed variables can significantly increase the cost of reading/writing them if the packed variables are not usually used together. For example, if we need to read a variable very often without reading its packed partner, it might be best to not tightly pack the variables. This is a design consideration developers must take into account when writing contracts.

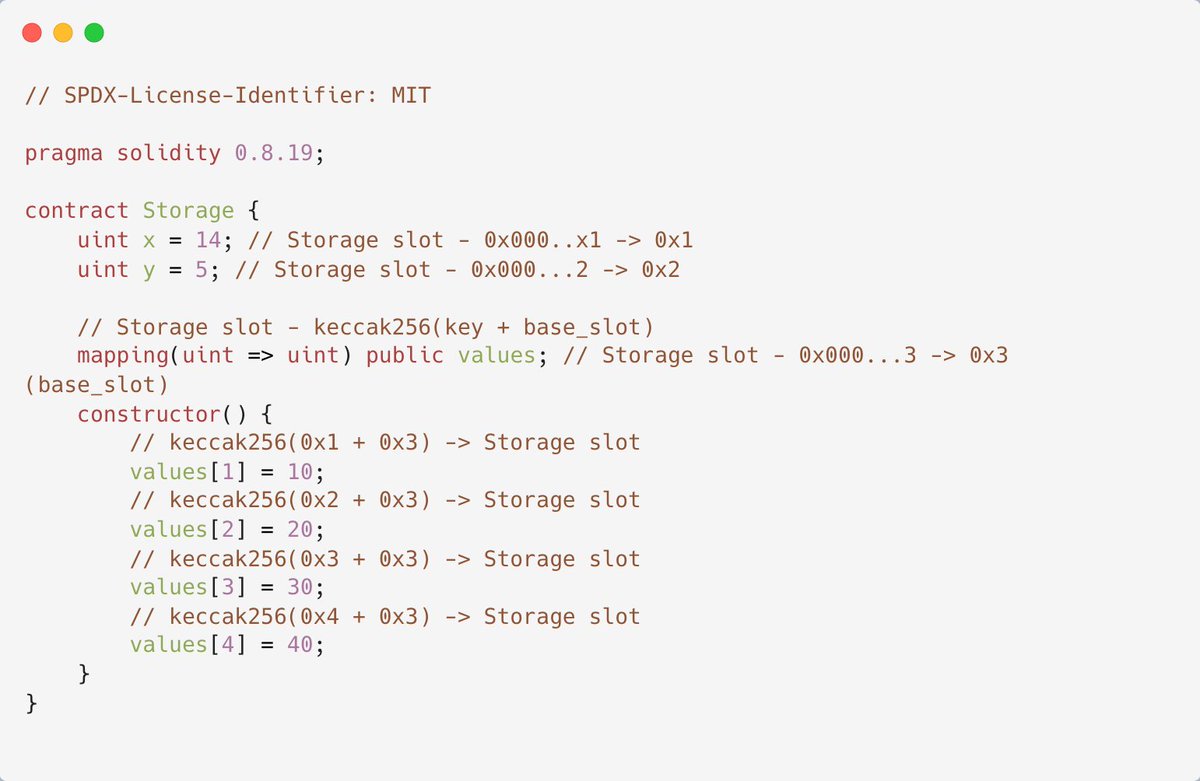

For mappings, the marker slot only marks the fact that there is a mapping (base slot). To find a value for a given key, the formula keccak256(base slot + key) is used. We can understand it better through the following example:

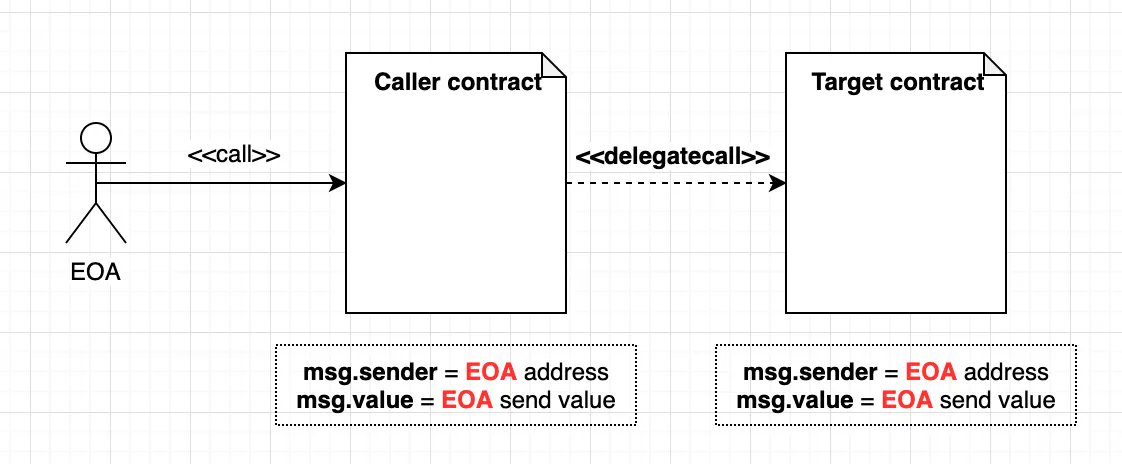

There exists a special variant of a message call, named delegatecall which is identical to a message call apart from the fact that the code at the target address is executed in the context (i.e. at the address) of the calling contract and msg.sender and msg.value do not change their values.

This means that a contract can dynamically load code from a different address at runtime. Storage, current address and balance still refer to the calling contract, only the code is taken from the called address.

This makes it possible to implement the “library” feature in Solidity: Reusable library code that can be applied to a contract’s storage, e.g. in order to implement a complex data structure.

delegatecall, as the name implies, is the calling mechanism of how caller contract calls target contract function but when the target contract executes its logic, the context is not on the user who executed the caller contract but on the caller contract.

Then when contract delegatecall to target, how the state of storage would be changed?

Because when delegatecall to target, the context is on Caller contract, all state change logics reflect on Caller’s storage.

For example, let there is Proxy contract and Business contract. Proxy contract delegatecall to Business contract function. If the user calls Proxy contract, Proxy contract will delegatecall to Business contract and function would be executed. But all state changes will be reflected Proxy contract storage, not a Business contract.

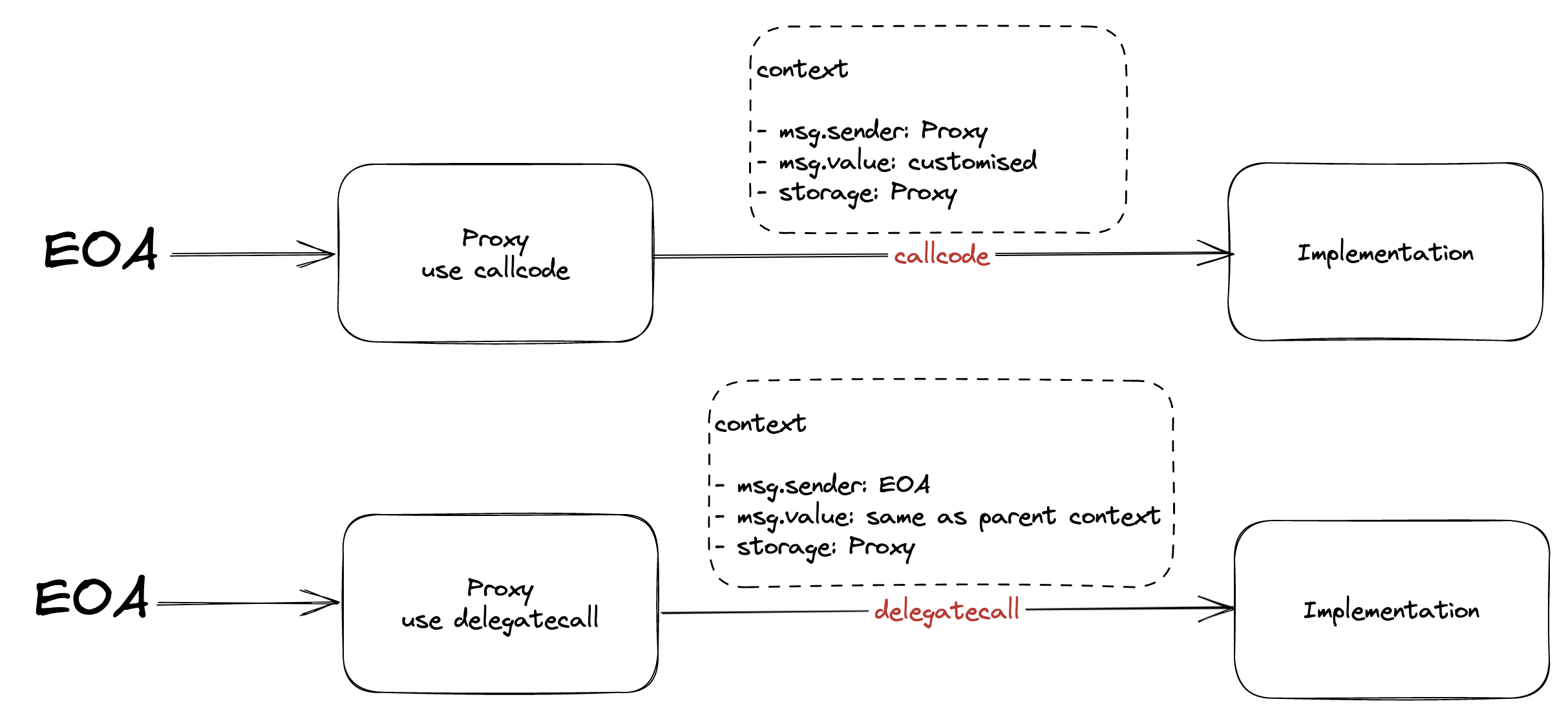

Both callcode and delegatecall have the same behavior on storage. That is, both of them can execute the implementation’s code and perform operations with proxy’s storage. The difference between them is in msg.value and msg.sender. In callcode, msg.value can be customized to hold a new value in the implementation contract and msg.sender is changed to Proxy’s address. In delegatecall, both msg.value and msg.sender remain the same in the proxy and implementation contracts.

The proxy itself is not inherently upgradeable, but it is the basis for just about all upgradeable proxy patterns. Calls made to the proxy contract are forwarded to the implementation contract using delegatecall. The implementation contract is also referred to as the logic contract.

In some variants, calls to the proxy are only forwarded if the caller matches an “owner” address.

Implementation address - Immutable in the proxy contract.

Upgrade logic - There is no upgradeability in a pure proxy contract.

Contract verification - Works with Etherscan and other block explorers.

Use cases

- Useful when there is a need to deploy multiple contracts whose code is more or less the same.

Pros

- Inexpensive deployment.

Cons

- Adds a single delegatecall cost to each call.

Examples

- Uniswap V1 AMM pools

- Synthetix

Known vulnerabilities

- Delegatecall and selfdestruct not allowed in implementation.

Most modern day proxies are initializeable. One of the main benefits of using a proxy is that you only have to deploy the implementation contract (AKA the logic contract) once, and then you can deploy many proxy contracts that point at it. However, the downside to this is that you cannot use a constructor in the already deployed implementation contract when creating the new proxy.

Instead, an initialize() function is used to set initial storage values.

Use cases

- Most proxies with any kind of storage that needs to be set upon proxy contract deployment.

Pros

- Allows initial storage to be set at time of new proxy deployment.

Cons

- Susceptible to attacks related to initialization, especially uninitialized proxies.

Examples

- This feature is used with most modern proxy types including TPP and UUPS, except for use cases where there is no need to set storage upon proxy deployment.

Known vulnerabilities

- Uninitialized proxy

Further Reading

The Upgradeable Proxy is similar to a Proxy, except the implementation contract address is settable and kept in storage in the proxy contract. The proxy contract also contains permissioned upgrade functions. One of the first upgradeable proxy contracts was written by Nick Johnson in 2016.

For security, it is also recommended to use a form of access control to differentiate between the owner/caller and the admin with permission to upgrade the contract.

Implementation address - Located in proxy storage.

Upgrade logic - Located in the proxy contract.

Contract verification - Depending on the exact implementation, it may not work with block explorers like Etherscan.

Use cases

- A minimalistic upgrade contract. Useful for learning projects.

Pros

- Reduced deployment costs through use of the Proxy.

- Implementation contract is upgradeable.

Cons

- Prone to storage and function clashing.

- Less secure than modern counterparts.

- Every call incurs cost of delegatecall from the Proxy.

Known vulnerabilities

- Delegatecall and selfdestruct not allowed in implementation

- Uninitialized proxy

- Storage collision

- Function clashing

Further reading

This is the “solution” to storage collisions.

This is similar to the Upgradeable Proxy, except that it reduces risk of storage collision by using the unstructured storage pattern. It does not store the implementation contract address in slot 0 or any other standard storage slot.

A problem that quickly comes up when using proxies has to do with the way in which variables are stored in the proxy contract. Suppose that the proxy stores the logic contract’s address in its only variable address public _implementation;. Now, suppose that the logic contract is a basic token whose first variable is address public _owner. Both variables are 32 byte in size, and as far as the EVM knows, occupy the first slot of the resulting execution flow of a proxied call. When the logic contract writes to _owner, it does so in the scope of the proxy’s state, and in reality writes to _implementation. This problem can be referred to as a "storage collision".

There are many ways to overcome this problem, and the "unstructured storage" approach which OpenZeppelin Upgrades implements works as follows. Instead of storing the _implementation address at the proxy’s first storage slot, it chooses a pseudo random slot instead. This slot is sufficiently random, that the probability of a logic contract declaring a variable at the same slot is negligible. The same principle of randomizing slot positions in the proxy’s storage is used in any other variables the proxy may have, such as an admin address (that is allowed to update the value of _implementation), etc.

OpenZeppelin contracts use the keccak-256 hash of the string “eip1967.proxy.implementation” minus one*. Because this slot is widely used, block explorers can identify and handle when proxies are being used.

*The minus provides additional safety because without it, the slot has a known preimage, but after subtracting 1, the preimage is unknown. For a known preimage, the storage slot may be overwritten via a mapping for example, where storage slot for its key is determined using a keccak-256 hash.

EIP-1967 also specifies a slot for admin storage (auth) as well as Beacon Proxies.

Implementation address - Located in a unique storage slot in the proxy contract.

Upgrade logic - Varies based on implementation.

Contract verification - Yes, most EVM block explorers support it.

Use cases

- When you need more security than the basic Upgradeable Proxy.

Pros

- Reduces risk of storage collisions.

- Block explorer compatibility

Cons

- Susceptible to function clashing.

- Less secure than modern counterparts.

- Every call incurs cost of delegatecall from the Proxy.

Known vulnerabilities

- Delegatecall and selfdestruct not allowed in implementation

- Uninitialized proxy

- Function clashing

Further reading

Note - This is replaced by EIP-2535 Diamond Standard.

This is the “solution” to function clashing.

As explained, proxies work by delegating all calls to a logic contract that holds the actual code to be executed. Nevertheless, upgradeable proxies require certain functions for management of the proxy itself. At the very least, an upgradeTo(address newImplementation) function is needed in order to be able to upgrade the proxy to a new logic contract.

This raises the question of how to proceed if the logic contract also has a function with the same name and signature. Upon a call to upgradeTo, did the caller intend to call the proxy management function or the logic contract? This ambiguity can lead to unintended errors, or even malicious exploits.

The clashing can also happen among functions with different names. Every function that is part of a contract’s public interface is identified at the bytecode level by a short 4-byte identifier. This identifier depends on the name and arity of the function, but since it’s only 4 bytes, there’s a possibility that two different functions with different names may end up actually having the same identifier. The Solidity compiler tracks when this happens within the same contract, but not when the collision happens across different ones, such as between a proxy and its logic contract.

The solution

The way we deal with this problem is via the transparent proxy pattern. The goal of a transparent proxy is to be indistinguishable by a user from the actual logic contract. This means that a user calling upgradeTo on a proxy should always end up executing the function in the logic contract, not the proxy management function.

How do we allow proxy management, then? The answer is based on the message sender. A transparent proxy will decide which calls are delegated to the underlying logic contract based on the caller address:

- If the caller is the admin of the proxy, the proxy will not delegate any calls, and will only answer management messages it understands.

- If the caller is any other address, the proxy will always delegate the call, no matter if it matches one of the proxy’s own functions.

This is similar to the Upgradeable Proxy and usually incorporates EIP-1967, but, if the caller is the admin of the proxy, the proxy will not delegate any calls, and if the caller is any other address, the proxy will always delegate the call, even if the function signature matches one of the proxy’s own functions.

Implementation address - Located in a unique storage slot in the proxy contract (EIP-1967).

Upgrade logic - Located in the proxy contract with use of a modifier to re-route non-admin callers.

Contract verification - Yes, most EVM block explorers support it.

Use cases

- This pattern is very widely used for its upgradeability and protections against certain function and storage collision vulnerabilities.

Pros

- Eliminates possibility of function clashing for admins, since they are never redirected to the implementation contract.

- Since the upgrade logic lives on the proxy, if a proxy is left in an uninitialized state or if the implementation contract is selfdestructed, then the implementation can still be set to a new address.

- Reduces risk of storage collisions from use of EIP-1967 storage slots.

- Block explorer compatibility.

Cons

- Every call not only incurs runtime gas cost of delegatecall from the Proxy but also incurs cost of SLOAD for checking whether the caller is admin.

- Because the upgrade logic lives on the proxy, there is more bytecode so the deploy costs are higher.

Examples

- dYdX

- USDC

- Aztec

Known vulnerabilities

- Delegatecall and selfdestruct not allowed in implementation

- Uninitialized proxy

- Storage collision

Further reading

What if we move the upgrade logic to the implematation contract?

EIP-1822 describes a standard for an upgradeable proxy pattern where the upgrade logic is stored in the implementation contract. This way, there is no need to check if the caller is admin in the proxy at the proxy level, saving gas. It also eliminates the possibility of a function on the implementation contract colliding with the upgrade logic in the proxy.

The downside of UUPS is that it is considered riskier than TPP. If the proxy does not get initialized properly or if the implementation contract were to selfdestruct, then there is no way to save the proxy since the upgrade logic lives on the implementation contract.

The UUPS proxy also contains an additional check when upgrading that ensures the new implementation contract is upgradeable.

This proxy contract usually incorporates EIP-1967.

Implementation address - Located in a unique storage slot in the proxy contract (EIP-1967).

Upgrade logic - Located in the implementation contract.

Contract verification - Yes, most EVM block explorers support it.

Use cases

- Currently, this is the most widely used pattern to deploy upgradeable contracts.

Pros

- Eliminates risk of functions on the implementation contract colliding with the proxy contract since the upgrade logic lives on the implementation contract and there is no logic on the proxy besides the fallback() which delegatecalls to the impl contract.

- Reduced runtime gas over TPP because the proxy does not need to check if the caller is admin.

- Reduced cost of deploying a new proxy because the proxy only contains no logic besides the fallback().

- Reduces risk of storage collisions from use of EIP-1967 storage slots.

- Block explorer compatibility.

Cons

- Because the upgrade logic lives on the implementation contract, extra care must be taken to ensure the implementation contract cannot selfdestruct or get left in a bad state due to an improper initialization.

- Still incurs cost of delegatecall from the Proxy.

Examples

- Superfluid

- Synthetix

Known vulnerabilities

- Uninitialized proxy

- Function clashing

- Selfdestruct

Further reading

Most proxies discussed so far store the implementation contract address in the proxy contract storage. The Beacon pattern stores the address of the implementation contract in a separate “beacon” contract. The address of the beacon is stored in the proxy contract using EIP-1967 storage pattern.

With other types of proxies, when the implementation contract is upgraded, all of the proxies need to be updated. However, with the Beacon proxy, only the beacon contract itself needs to be updated.

Both the beacon address on the proxy as well as the implementation contract address on the beacon are settable by admin. This allows for many powerful combinations when dealing with large quantities of proxy contracts that need to be grouped in different ways.

The main idea behind the beacon contract is re-usability. If you have several proxies pointing to the same logic contract address then, every time you want to update the logic contract, you'd have to update all proxies. As this can become gas intensive, it would make more sense to have a beacon contract that returns the address of the logic contract for all proxies.

So, if you use beacons, you are having another layer of Smart Contract in between that returns the address of the actual logic contract.

Implementation address - Located in a unique storage slot in the beacon contract. The beacon address lives in a unique storage slot in the proxy contract.

Upgrade logic - Upgrade logic typically lives in the beacon contract.

Contract Verification - Yes, most EVM block explorers support it.

Use cases

- If there are multiple proxy contracts that can all be upgraded at once by upgrading the beacon.

- Appropriate for situations that involve large amounts of proxy contracts based on multiple implementation contracts. The beacon proxy pattern enables updating various groups of proxies at the same time.

Pros

- Easier to upgrade multiple proxy contracts at the same time.

Cons

- Gas overhead of getting the beacon contract address from storage, calling beacon contract, and then getting the implementation contract address from storage, plus the extra gas required by using a proxy.

- Adds additional complexity.

Examples

- USDC

- Dharma

Known vulnerabilities

- Delegatecall and selfdestruct not allowed in implementation

- Uninitialized proxy

- Function clashing

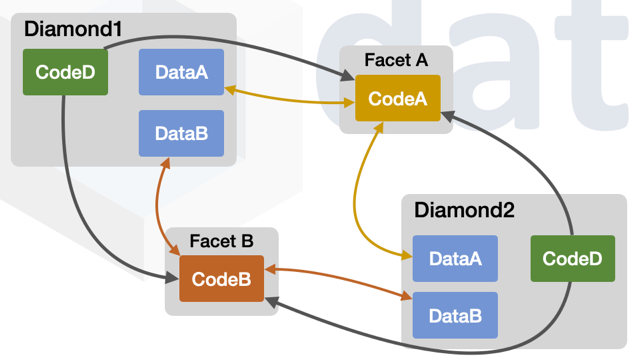

EIP-2535 “Diamonds” are modular smart contract systems that can be upgraded/extended after deployment, and have virtually no size limit. From the EIP:

"a diamond is a contract with external functions that are supplied by contracts called facets. Facets are separate, independent contracts that can share internal functions, libraries, and state variables."

The diamond pattern consists of a central Diamond.sol proxy contract. In addition to other storage, this contract contains a registry of functions that can be called on external contracts called facets.

Glossary of Diamond proxy uses a unique vocabulary:

This standard is an improvement of EIP-1538 (TPP). The same motivations of that standard apply to this standard.

A deployed facet can be used by any number of diamonds.

The diagram below shows two diamonds using the same two facets.

-

FacetA is used by Diamond1

-

FacetA is used by Diamond2

-

FacetB is used by Diamond1

-

FacetB is used by Diamond2

-

A diamond is a facade smart contract that delegatecalls into its facets to execute function calls. A diamond is stateful. Data is stored in the contract storage of a diamond.

-

A facet is a stateless smart contract or Solidity library with external functions. A facet is deployed and one or more of its functions are added to one or more diamonds. A facet does not store data within its own contract storage but it can define state and read and write to the storage of one or more diamonds. The term facet comes from the diamond industry. It is a side, or flat surface of a diamond.

-

A loupe facet is a facet that provides introspection functions. In the diamond industry, a loupe is a magnifying glass that is used to look at diamonds.

-

An immutable function is an external function that cannot be replaced or removed (because it is defined directly in the diamond, or because the diamond’s logic does not allow it to be modified).

-

A mapping for the purposes of this EIP is an association between two things and does not refer to a specific implementation.

Contract Verification - Contracts can be verified on Etherscan with the help of a tool called Louper.

Use cases

- A complex system where the highest level of upgradeability and modular interoperability is required.

Pros

- A stable contract address that provides needed functionality. Emitting events from a single address can simplify event handling.

- Can be used to break up a large contract > 24kb that is over the Spurious Dragon limit.

Cons

- Additional gas required to access storage when routing functions.

- Increased chance of storage collision due to complexity.

- Complexity may be too much when simple upgradeability is required.

Examples

- Simple DeFi

- PartyFinance

Known vulnerabilities

- Delegatecall and selfdestruct not allowed in implementation

Further reading

The below table compares the pros and cons of the diamond, transparent, and UUPS proxy patterns:

There isn't an automatic process to verify if the external contract is present when delegatecall is utilized. The return value will be true in the event that the external contract invoked is not present. This is noted in the solidity documentation in a cautionary note along with the following information:

The low-level functions call, delegatecall and staticcall return true as their first return value if the account called is non-existent, as part of the design of the EVM. Account existence must be checked prior to calling if needed.

Testing procedure

Determining the external contract address that the call is using is the first step. delegatecall may return true unexpectedly if there is a chance that there isn't a contract at this address and no check is made to make sure the contract is in place before the delegatecall.

When selfdestruct and delegatecall are used together, unforeseen edge cases can occur. In particular, contract A will be destroyed if contract B contains selfdestruct in its function and contract A has a delegatecall to it.

Testing procedure

It is simple to recognize this weakness. First, there is a significant overall security risk if a contract has a delegatecall that delegates to a user-provided address (like a function parameter in an external function).

Verify whether the target contract has a selfdestruct if a contract has a delegatecall to a hardcoded target contract. Check the contract to which the delegation is assigned for a selfdestruct (and carry on if another delegatecall is discovered) if the destination contract has a delegatecall but no selfdestruct. The original contract containing the delegatecall may be deleted if the target contract has a selfdestruct clause. Every clone made from this master contract will self-destruct if the EIP-1167 cloning master contract is employed.

CTF Example

Further Reading

Function clashing occurs when compiled smart contracts use a function selector, which is a 4-byte identifier that is obtained from the hash of the function name, to identify functions. When the first 32 bits of two functions' hashes match, they can have identical 4-byte identifiers despite having different names. The compiler will identify instances in which a 4 byte function selector appears twice in a single contract, but it won't stop it from happening in separate project contracts.

Most proxy types exhibit function clashing, although not all of them do. Because all of the custom functions are stored in the implementation contract, UUPS proxies in particular are typically not susceptible to function clashing.

Testing procedure

To test for this vulnerability, you can collect the function selectors of a proxy contract and implementation contract to compare them for any function clashing. One tool for this is solc, where solc --hashes MyContract.sol will list all function selectors. Slither has a Slither’s Function ID printer that can do the same thing. Slither also has a slither-check-upgradeability tool that can detect function clashing.

Further Reading

- Tincho Function Clashing Writeup

- Nomic Labs' Blog Post

- OpenZeppelin Docs Explaining Function Clashing

When the storage slot arrangement in the proxy contract and the implementation contract differ, a storage collision occurs. This is problematic because the variables in the implementation contract control where the data is kept, but the delegatecall in the proxy contract means that the implementation contract is using the proxy contract's storage. A storage collision may occur if the storage slots of the implementation contract and the proxy contract are not aligned.

Testing Procedure

There are many approaches to testing for this vulnerability. One way to test for this vulnerability is using the sol2uml tool. You can visualize the storage slots of the proxy contract and the implementation contract to see if they have any mismatches.

A second approach that is more programmatic is using slither-read-storage to collect the storage slots used by the proxy contract and the implementation contract, then comparing them.

A third approach is to find a tool that is designed to compare the storage slots of two contracts.

Slither has a slither-check-upgradeability tool that has several detectors for storage layout issues.

CTF Examples

- Solidity by Example

- Ethernaut Level 6 “Delegation”

- Ethernaut Level 16 “Preservation”

- Ethernaut Level 24 “Puzzle Wallet”

Further Reading

When a contract constructor is called automatically, why are proxies still required to have an initialize function? OpenZeppelin provides an explanation of the cause here. The constructor code of a contract is executed only once during deployment; however, the implementation contract's (also known as the logic contract) constructor code cannot be executed within the framework of the proxy contract. The constructor cannot be used for this purpose since the implementation contract's constructor function will always run in the context of the implementation contract. Instead, the implementation contract must save the value of the _initialized variable in the proxy contract context. Because the initialize call needs to go via the proxy, this is the reason the implementation contract has an initialize method. There is a potential race condition that should be addressed because the initialize call needs to occur independently of the implementation contract deployment. One way to prevent this race condition is to protect the initialize function with an address control modifier, limiting its ability to be initialized to a specific msg.sender.

A specific variant of the uninitialized UUPS proxy vulnerability is found in the OpenZeppelin library between version 4.1.0 and 4.3.2.

Testing Procedure

Find the storage slot of the initialized state variable or a comparable variable that the initialization function uses to reverse if this is not the function's first call in order to test for this vulnerability. When using the OpenZeppelin private _initialized variable from Initializable.sol, the contract has not been initialized if the _initialized value is zero, and it has been initialized if the value is one.

Slither has a slither-check-upgradeability tool that has several initializer issue detectors.

Further Reading

The below listed resources can be used as development guides to create upgradeable smart contracts using proxies:

- Writing Upgradeable Contracts by OpenZeppelin

- Proxy API by OpenZeppelin

- How to create a Beacon Proxy

- How to use the UUPS proxy pattern to upgrade smart contracts

- Offical ERC Releases

- OpenZeppelin

- yAcademy

- Solidity documentation