-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 59

Getting Started

I often find that I have a collection of objects which I want to present to the user in some sort of tabular format. It could be the list of clients for a business, a list of known FTP servers or even something as mundane as a list of files in a directory. User interface-wise, the ListView is the perfect control for these situations. However, I find myself groaning at the thought of using the ListView and secretly hoping that I can use a ListBox instead.

The reason for wanting to avoid the ListView is all the boilerplate code it needs to work: make the ListViewItems, add all the SubItems, catch the header click events and sort the items depending on the data type. When the user right clicks on the list, I have to figure out which rows are selected, and then maps those rows back into the model objects I am interested in. None of these tasks are obvious if you don’t already know the tricks, and even when you do, it is annoying to have to code them again for each ListView. If you want to support grouping, there’s an even bigger chunk of boilerplate code to copy and then modify slightly.

The ObjectListView was designed to take away all these repetitive tasks and so make a ListView much easier – even fun – to use.

There are two ways to use an ObjectListView in your project:

- Use the ObjectListView project

- Download the ObjectListView project

- Add the ObjectListView project to your project (right click on your solution; choose “Add...”, “Existing Project”, then choose the ObjectListView.csproj)

- In your project, add a reference to the ObjectListView project (right click on your project; choose “Add Reference...”, choose “Projects” tab; then double click on the ObjectListView project)

- Build your project

- Once your project has been built, there should now be a new section in your Toolbox, “ObjectListView Components”. In that section should be ObjectListView and its friends. (If you are using SharpDevelop, the section is called “Custom Components” and it appears at the bottom of the toolbox.) You can then drag an ObjectListView onto your window, and use it as you would a standard ListView control.

- Use ObjectListView.dll

- If you don’t want to add the ObjectListView project to your project, you can also just add the ObjectListView.dll file.

- Download or build the ObjectListView.dll file.

- In your project, add a reference to the ObjectListView.dll (right click on your project; choose “Add Reference...”, choose “Browse” tab; navigate to the ObjectListView.dll file and double click on it).

- Adding the dll does not automatically add any new components into your toolbox. You will need to add them manually after you have added the dll to your project.

If you are a visual person, the process I’m about to explain is this:

You give the ObjectListView a list of model objects. It extracts aspects from those objects, converts those aspects to strings, and then builds the control with those strings.

Keep this image in mind when reading the following text.

This is important. You need to understand this.

Before you start trying to use an ObjectListView, you should understand that the process of using one is different to the process of using a normal ListView. A normal ListView is essentially passive: it sits there, and you poke and prod it and eventually it looks like you want. An ObjectListView is much more active. You tell it what you want done and the ObjectListView does it for you.

An ObjectListView is used declaratively: you state what you want the ObjectListView to do (via its configuration), then you give it your collection of model objects, and the ObjectListView does the work of building the ListView for you.

This is a different approach to using a ListView. You must get your mind around this, especially if you have done any ListView programming before (See [Unlearn you must]].

The crucial part of using an ObjectListView is configuring it. Most of this configuration can be done within the IDE by setting properties on the ObjectListView itself or on the columns that are used within the list. Some configuration cannot be done through properties: these more complex configurations are done by installing delegates (more on this later).

Once the columns and control are configured, putting it into action is simple. You give it the list of model objects you want it to display, and the ObjectListView will build the ListView for you:

this.myFirstOlv.SetObjects(myListOfSongs);

What’s this “model” you keep talking about?

Your model objects are the data used by your application. They are the part that stays the same when you decide make your desktop application available as a web app, or vice versa. The view is the part that presents your model objects to the user. The view changes completely when you move your application to the web.

For more detailed discussion, see [here]] or any other of the thousand sites that discuss this.

This section is for those who are familiar with using a ListView.

This section is for those who are familiar with using a ListView, either from .NET or (shudder) from Petzold-style windows. Complete novices can skip this section.

For those of you who have struggled with a ListView before, you must unlearn. An ObjectListView is not a drop in replacement for a ListView. If you have an existing project, you cannot simply create an ObjectListView instead of creating a ListView. An ObjectListView needs a different mindset. If you can perform the mind-mangling step of changing your thinking, ObjectListView will be your best friend.

Beware of ListViewItems. You never need to add ListViewItems to an ObjectListView. If you find yourself adding things to the Items collection, creating ListViewItems, or adding sub-items to anything, then you need to stop – you are being seduced to the dark side. An ObjectListView does all that work for you. It owns the ListViewItems and will destroy and recreate them as needed. Your job is to tell the ObjectListView what information you want the ListViewItems to contain, and then to give it the list of objects to show.

Resist the temptation to add, edit, remove, or otherwise mess with ListViewItems – it will not work.

There is also no need to hide information in a ListViewItem. Old style ListView programming often required attaching a key of some sort to each ListViewItem, so that when the user did something with a row, the programmer would know which model object that row was related to. This attaching was often done by creating one or more zero-width columns, or by setting the Tag property on the ListViewItem.

With an ObjectListView, you do not need to do this. The ObjectListView already knows which model object is behind each row. In many cases, the programmer simply uses the SelectedObjects property to find out which model objects the user wants to do something to.

For the purposes of this introduction, we’ll imagine that you are writing an application to manage a music library. One of your central model object might be Song, which could looks something like this:

class Song {

public Song () {

}

public string Title {

get { ... };

set{ ... };

}

public DateTime LastPlayed {

get { ... };

set{ ... };

}

public float GetSizeInMb {

...

}

public int Rating {

get { ... };

set{ ... };

}

...

}

You can download all the projects and source used in this getting started section here: [getting-started.zip (250 KB)]].

The first configuration step is to tell each column which bit (called an “aspect”) of your model object it is going to display. You do this through a Columns properties. You can edit the Columns of an ObjectListView by either:

- Finding the Columns property of the ObjectListView and clicking the ellipsis (...) button next to it;

- Or by showing the quick commands for the ObjectListView (press on the small arrow at the top right of the control) and clicking “Edit Columns.”

You should now see a dialog entitled “OLVColumn Collection Editor.” Click “Add” to add a new column to the ObjectListView. Once you have a column selected, all its properties are presented on the right hand side (I find it helpful to resize the dialog so I can see all the properties at once).

At the top of the list of properties is a property AspectName. This is the property that tells the column which aspect of the model object it should display. The AspectName will hold the name of the property, method or field that will be shown in this column.

To show the Song’s title in the first column, you set the first column’s AspectName to “Title”.

OK, we’ve told our first column which bit of data it should display. For the Title, this is all that is necessary. But for our second column which will show LastPlayed, there is another configuration we should consider: converting our bit of data to a string.

A ListView control can only display strings. Everything else - booleans, integers, dates, whatever - has to be converted to a string before it can be given to the ListView. By default, the ObjectListView converts data to strings like this:

stringForDisplay = String.Format("{0}", aspectValue);

You can use a different format string (instead of the default “{0}”) by setting the AspectToStringFormat property. If the AspectToStringFormat property isn’t empty, its value will be used as the format string instead of “{0}”. See String.Format() documentation to understand its abilities. Some useful format strings are “{0:d}” to show a short date from a DateTime value, and “{0:C}” for currency values.

So, we would configure our second column like this: AspectName: “LastPlayed”, AspectToStringFormat: “{0:d}”.

Our third column is to display the GetSizeInMb aspect. We’d like this to put commas into its string representation, so we would configure it like this: AspectName: “GetSizeInMb”, AspectToStringFormat: “{0:#,##0.0}”.

Our fourth column is to display the Rating aspect. It does not need a special AspectToStringFormat, so it would simply be configured with AspectName: “Rating”.

Having finished our IDE configuration, we set the whole thing into action with our one line of code:

this.olvSongs.SetObjects(listOfSongs);

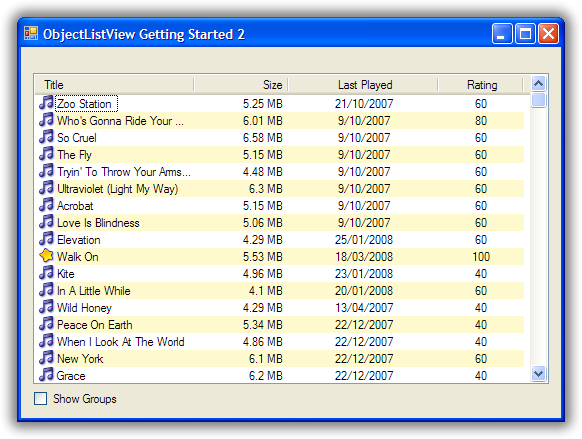

And we should get something like this:

Underwhelmed? Admittedly, it’s not much to look at, but be patient. Also, consider how much work you had to do to make it happen: some IDE configuration and one line of code. It doesn’t look so bad now, does it?

With those column definitions, we have a ListView that shows the title, date last played, size (in megabytes) and rating of various tracks in your music library. But, actually, we have quite a bit more than that. Without any extra work, sorting, grouping, search by typing and column selection all work:

- Clicking on the column headers will sort and reverse sort the rows. The sort is accurate for the data type: when sorting by size, a song of 35 megabytes will come after a song of 9 megabytes.

- If you enable groups on the ListView (set ShowGroups to True), the ListView will group the rows according to the column clicked.

- If you type a couple of letters, the row that matches the typed letters will be selected. The rows are matched on the sort column values, not the first column values.

- If you right click on the column headers, a menu will popup which allows you to select which columns are visible.

OK, that’s good, but any real ListView needs to be able to put little icons next to the text. That is our next task.

Deciding which icon to put in a column cannot be done in the IDE. Very often the icon used depends on the model object being displayed. To decide on an icon, we need a more complex type of configuration: installing a delegate.

A delegate is basically a piece of code that you give to an ObjectListView saying, “When you need to do this, call this piece of code” where this can be any of several tasks. In this case, we install an ImageGetter delegate, which tells the ObjectListView, “When you need to figure out the image for this model object, call this piece of code.”

If the word “delegate” worries you, think of them as function pointers where the parameter and return types can be verified. If that makes no sense to you, just keep reading. It will (possibly) become clear with some examples.

First, you need a method that matches the ImageGetterDelegate signature: it must accept a single object parameter and returns an object. A completely frivolous example might be like this, which displays a star image if the song has a rating 80 or higher and a normal song icon otherwise:

public object SongImageGetter(object rowObject) {

Song s = (Song)rowObject;

if (s.Rating >= 80)

return "star";

else

return "song";

};

You install this delegate by assigning it to the ImageGetter property on the first column:

this.titleColumn.ImageGetter = new ImageGetterDelegate(this.SongImageGetter);

The delegate is passed a parameter of type object. The ObjectListView doesn’t know anything about your model objects, not even their class. It only ever deals with them as object. In your delegates, casting rowObject to an instance of your model will almost always be the first step (but see TypedObjectListView for an alternative).

The value returned from the ImageGetter delegate is used as an index into the ObjectListView‘s SmallImageList. As such, the ImageGetter can return either a string or an int. (If the ObjectListView is owner-drawn, the ImageGetter can return an Image, but that’s a story for another day).

The ImageGetter delegate is installed on the column, since each column can have its own image.

.NET 2.0 added the convenience of anonymous delegates (to C# at least – VB users are stuck with using separate methods). In an anonymous delegates, the code for the function is inlined, like this:

this.titleColumn.ImageGetter = delegate (object rowObject) {

Song s = (Song)rowObject;

if (s.Rating >= 80)

return "star";

else

return "song";

};

For small methods, anonymous delegate are much more convenient.

Another useful delegate that you can install is the AspectToStringConverter delegate. Sometimes, converting a bit of the model (the Aspect) to a string can be more than String.Format() can handle. AspectToStringConverter takes over when String.Format() is not enough.

In our Song class, the actual size of the song is stored as long SizeInBytes. It would be nice if we could show the size as “360 bytes”, “901 KB”, or “1.1 GB” which ever was more appropriate.

To do something smarter like this, we would change the AspectName of our third column to be “SizeInBytes” and install a AspectToStringConverter delegate, like this:

this.sizeColumn.AspectToStringConverter = delegate(object x) {

long size = (long)x;

int[] limits = new int[] { 1024 * 1024 * 1024, 1024 * 1024, 1024 };

string[] units = new string[] { "GB", "MB", "KB" };

for (int i = 0; i < limits.Length; i++) {

if (size >= limits[i])

return String.Format("{0:#,##0.##} " + units[i], ((double)size / limits[i]));

}

return String.Format("{0} bytes", size); ;

};

Just a couple more things to configure. You need to make an ImageList, give it the images you want, and then assign it to the SmallImageList property of the ObjectListView. And finally, we will set the UseAlternatingBackColors property to true.

Putting all these bits together, we now have something that looks like this:

Hey! That’s starting to not look too bad.

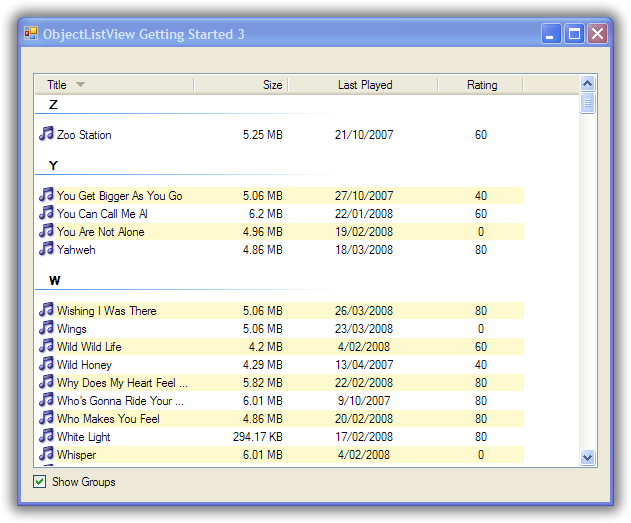

The last part of our getting started project will be to improve how the ObjectListView displays groups.

If you turn on the ShowGroups property on the ObjectListView, you will see that it automatically supports grouping. Normally, the first column groups rows that have the same initial letter. You can give other columns this same behaviour by setting the UseInitialLetterForGroup property to true.

-

Quite a lot happens under the hood when grouping is enabled. When the ObjectListView is rebuilt:

A group “key” is calculated for each model object. All model objects that return the same “key” are placed in the same group. That group “key” is then converted to a string. This string becomes the label for the group. Each group of model objects is then sorted The sorted objects added beneath their group’s label.

The crucial part to understand is that all model objects that have the same “key” are placed in the same group. By default, the “key” is the aspect of the model object as calculated by the grouping column. So when grouping is enabled and the user clicks the “Size” column, the Songs are grouped by their SizeInBytes value, that is, all Songs that have exactly the same number of bytes are placed in the same group.

The default way of calculating the group key works, but it can be improved. You can do your own calculation by (you guessed it) installing a delegate, the GroupKeyGetter delegate.

We need to improve the way the “Last Played” column is grouped. The default group key for this column is the value of the LastPlayed property for each Song. This is not very useful - every song ends up in its own group. (If you can explain why, well done! You’re right on the ball). Worse, when the key is converted to a label, only the date part is displayed, so it looks as if your control is broken.

We’ll change the “Last Played” column so that it groups songs by the month they were last played – all the songs last played in July should be in the same group. To do this, we install a GroupKeyGetter on the lastPlayedColumn:

this.lastPlayedColumn.GroupKeyGetter = delegate(object rowObject) {

Song song = (Song)rowObject;

return new DateTime(song.LastPlayed.Year, song.LastPlayed.Month, 1);

};

This will group the songs by just their year and month. We also install another delegate that will convert our group key into a string that will be used as the label for the group:

this.lastPlayedColumn.GroupKeyToTitleConverter = delegate(object groupKey) {

return ((DateTime)groupKey).ToString("MMMM yyyy");

};

With these two simple delegates in place, now grouping by the “Last Played” column looks much better.

Why does ObjectListView have these two steps: key getting and key to title? Isn’t it simpler to just group model objects by their group label?

Because we want to be able to sort the groups themselves correctly. To do this we need to have the actual group key, not just the group label. For example, with our LastPlayed column, the group “January 2008” should appear before the group “February 2008.” But that’s not possible if we only have the group labels. So we need the two-step tango.

The “Last Played” column now groups nicely. Let’s see what we can do with the “Rating” column. The Rating is a number between 0 and 100 where 0 means “Should be deleted” and 100 means “Should be played continuously through all available loudspeakers”.

For our example, we’ll group them like this:

| <=20 | “Why do you even have these songs?” |

|---|---|

| 21-39 | “Passable I suppose” |

| 40-79 | “Buy more like these” |

| 80-100 | “To be played continuously” |

We could do this by installing a GroupKeyGetter and a GroupKeyToTitleConverter, but this is such a common use case, there’s a special function to do it for you: MakeGroupies(). We’ll use this method like this:

this.ratingColumn.MakeGroupies(

new int[] { 20, 39, 79 },

new string[] { "Why do you even have these songs?", "Passable I suppose",

"Buy more like these", "To be played continuously" }

);

The first array contains the cutoff points. Every group key less than or equal to the first cutoff point goes into one group. Keys greater than the first cutoff but less than or equal to the second cutoff go into another group, and so on. A group key greater than the last cutoff goes into yet another group.

The second array contains the group labels for the matching cutoff point. This array must have one more item than the cutoff point array. This last item is the label for the group whose keys were greater than the last cutoff value.

So with our Songs, songs that have a Rating of less than or equal to 20 go into a group labelled “Why do you even have these songs?”. Songs with a Rating between 21 and 39 go into a second group labelled “Passable I suppose”. Songs with a Rating 80 and above fall into the last group labelled “To be played continuously”.

It’s a bit complicated to explain, but it’s quite easy to use.

With the MakeGroupies() in place, grouping by our Rating column, now looks like this:

Well done! You’ve made it to the end of the tutorial. You should by now have a reasonable grasp of some of the things an ObjectListView can do, and how to use it in your application.

If you need further help, you can look at the [Cookbook]] for those questions that just don’t have answer anywhere else.

Don’t forget: Use The Source Luke! You have all the source code. If you can’t figure something out, read the code and see what is actually happening.

[Welcome To The New World of Loving .NET’s ListView]]